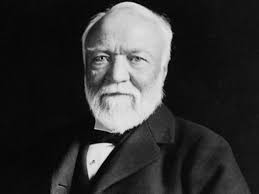

Andrew Carnegie (November 25, 1835 – August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist, steel magnate, and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in history.

The Carnegie family had left their home in Scotland and come to America when Andrew was 13. Andrew worked first in an American textile factory, then as a Morse code telegrapher, and then for the railroads. He served as an assistant on the Pennsylvania Railroad in the 1850s while still in his 20s. There, he learned sophisticated business management techniques—dealing with distributed assets, levels of trustworthiness, strict accountability, unforeseen problems, and cost-effectiveness. He showed a great talent for buying successful stocks, taking advantage of what we now call insider trading, which was then legal.

He built Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Steel Company, which he sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $303,450,000. It became the U.S. Steel Corporation. After selling Carnegie Steel, he surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American for the next several years.

With the fortune he made from business, he built Carnegie Hall in New York, NY, and the Peace Palace and founded the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, Carnegie Hero Fund, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, among others.

The “Andrew Carnegie Dictum” was:

- To spend the first third of one’s life getting all the education one can.

- To spend the next third making all the money one can.

- To spend the last third giving it all away for worthwhile causes.

Rags to Riches

In David Nasaw’s Biography of Andrew Carnegie, he writes:

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835, the eldest son of a failed linen weaver and an entrepreneurially minded mother who kept shop and took in work from local shoemakers to put food on the table.

At age thirteen, after no more than a year or two of formal schooling, young Andrew set sail with mother, father, and younger brother for America. Poor though the Carnegies were, they were supported by his mother’s extended family and by the Scottish emigrants who had preceded them to America and Allegheny City, across the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh. Andra, as he was called, was put to work as a bobbin boy at a cotton mill, but after less than a year in the mill, found work as a telegraph messenger, taught himself Morse code, and was hired as private telegraph operator and secretary to Thomas A. Scott, the Pittsburgh division superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. For the next twelve years or so, he would work for the railroad.

At age thirty, Carnegie resigned his position to go into business for himself with his former bosses, Tom Scott and J. Edgar Thomson, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Together, they organized a series of companies—with Scott and Thomson as secret partners—that were awarded insider contracts to supply the Pennsylvania Railroad with raw materials and build its iron bridges. By his early thirties, Carnegie had, with help and investment capital from his friends, accumulated his first fortune—in Pennsylvanian oil wells, iron manufacturing, bridge building, and bond trading.

Life Long Learner

His ultimate goal was to establish himself as a man of letters, as well known and respected for his writing and intellect as for his ability to make money. He had as a child and young man read widely and memorized large portions of Robert Burns’s poetry and Shakespeare’s plays. In New York and London, he continued his self-education.

He befriended some of the English-speaking world’s most renowned men of letters, among them Herbert Spencer, Matthew Arnold, Richard Watson Gilder, editor of the Century magazine, and Sam Clemens; published regularly in respected journals of opinion on both sides of the Atlantic; wrote two well-received travelogues and a best-selling book entitled Triumphant Democracy, and with his “Gospel of Wealth” essays established himself as the moral philosopher of industrial capitalism.

Charity

On retirement, he accelerated his giving to communities for library buildings and church organs so that parishioners could be introduced to classical music. He also set up a number of charitable trusts, each charged with a specific task: free tuition for Scottish university students; pensions for American college professors; a scientific research institution in Washington, D.C.; a library, music hall, art gallery, and natural history museum in Pittsburgh; a Hero Fund for civilians; a “peace endowment.

Only as he approached his later seventies did he realize that, with his payout from selling Carnegie Steel at 5 percent a year on more than $200 million, he was running out of time to give away his fortune. Disheartened that he would fail at the most important task he had taken on—to wisely give back to the community the millions he had accumulated—he established the Carnegie Corporation to receive and disperse whatever was left behind when he died.

World Peace

He had entered retirement intending to devote all his time and efforts to his philanthropy. But his last years were consumed with another cause: world peace. Arguing against his own self-interest—Carnegie Steel made millions manufacturing steel armor plate for the U.S. Navy—he campaigned for naval disarmament, then an international court, a league of peace, and treaties of arbitration between the nations of Europe and the United States.

With considerable rhetorical power, he opposed American intervention in the Philippines and the British war with the Boer Republics in South Africa. As the European nations, followed closely by the United States, entered into an escalating naval arms race, he inserted himself into the diplomatic mix as an insider with access to the White House and Westminster. He would spend the rest of his days as an outspoken “apostle of peace,” commuting back and forth between his homes in New York and Scotland and the world’s capitals.

Only at age eighty, in the second year of the Great War, did he recognize that his efforts had been in vain. He spent his last years in silence, isolated from his friends, unable to return to his home in Scotland, his optimism shattered.

In his book, The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J. P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy, Charles R. Morris writes about Andrew Carnegie:

His rise is the canonical American rags-to-riches tale. Carnegie’s father was a displaced Scottish hand-loom weaver, and the family emigrated to Pittsburgh when Andrew was thirteen. Andrew zipped through jobs as a bobbin boy, a bookkeeper’s clerk, and a telegraph delivery boy, where he picked up telegraphy by watching the operators. He quickly became the business community’s favorite telegrapher, and then a one-man wire service, compiling each day’s telegraphic news reports for Pittsburgh’s newspapers.

He was as relentless in self-improvement as in everything else, reading voraciously, and working hard on his accent and grammar.

“His life was dominated by his mother, Margaret, who imparted the fierce class consciousness of the respectable poor—a wrenching shame of poverty and withering scorn for the unambitious laboring people they were forced to associate with. She and Andrew were inseparable until she died, just before his fifty-first birthday. The Carnegies were nonbelievers, but Andrew still inherited a strong Calvinist aversion to fleshly pleasures. He was immensely charming, and had many friendly associations with women, but probably no intimacy until he finally married a few months after his mother’s death, to a young lady who had waited years for that blessed event.”

Andrew’s big break came when he was seventeen, in the person of Tom Scott, who became his business hero. Scott was one of the era’s great railroad executives. Born poor, and working since age ten, he immediately took to Andrew. The need to track far-flung rolling stock made railroads heavy telegraph users, and Scott, who had just been appointed superintendent of the Western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad, was a frequent visitor to Andrew’s telegraph office. When he decided that the workload justified a telegraph station of his own, his first choice for an operator was that bright, bustling little “Andy.”

Highly Read

Carnegie was so spectacularly talented—with his extraordinary intelligence and dead-accurate Scots practicality, his energy, his immense charm, his feline instinct for a deal—that he simply overmatched everyone else. He was also far better read than most of his peers, with an acquired, but genuine, taste for art and culture, and an attractive writing style. Indeed, he constantly questioned whether he was squandering his talents in business.

The Gospel of Wealth

“The Gospel of Wealth”, is an article written by Andrew Carnegie in June of 1889 that describes the responsibility of philanthropy by the new upper class of self-made rich. The article was published in the North American Review, an opinion magazine for America’s establishment. It was later published as “The Gospel of Wealth” in the Pall Mall Gazette.

Carnegie proposed that the best way of dealing with the new phenomenon of wealth inequality was for the wealthy to utilize their surplus means in a responsible and thoughtful manner. This approach was contrasted with traditional bequest (patrimony), where wealth is handed down to heirs, and other forms of bequest e.g. where wealth is willed to the state for public purposes. Benjamin Soskis, a historian of philanthropy, refers to the article as the ‘urtext’ of modern philanthropy.

At the age of 35, Carnegie decided to limit his personal wealth and donate the surplus to benevolent causes. He was determined to be remembered for his good deeds rather than his wealth. He became a “radical” philanthropist.

On Love of Reading

In his Autobiography, Andrew Carnegie wrote:

Colonel James Anderson—I bless his name as I write—announced that he would open his library of four hundred volumes to boys, so that any young man could take out, each Saturday afternoon, a book which could be exchanged for another on the succeeding Saturday.

My dear friend, Tom Miller, one of the inner circle, lived near Colonel Anderson and introduced me to him, and in this way the windows were opened in the walls of my dungeon through which the light of knowledge streamed in. Every day’s toil and even the long hours of night service were lightened by the book which I carried about with me and read in the intervals that could be snatched from duty. And the future was made bright by the thought that when Saturday came a new volume could be obtained. in this way I became familiar with Macaulay’s essays and his history, and with Bancroft’s “History of the United States,” which I studied with more care than any other book I had then read. Lamb’s essays were my special delight, but I had at this time no knowledge of the great master of all, Shakespeare, beyond the selected pieces in the school books. My taste for him I acquired a little later at the old Pittsburgh Theater.

John Phipps, James R. Wilson, Thomas N. Miller, William Cowley—members of our circle—shared with me the invaluable privilege of the use of Colonel Anderson’s library. Books which it would have been impossible for me to obtain elsewhere were, by his wise generosity, placed within my reach; and to him I owe a taste for literature which I would not exchange for all the millions that were ever amassed by man. Life would be quite intolerable without it.

Nothing contributed so much to keep my companions and myself clear of low fellowship and bad habits as the beneficence of the good Colonel. Later, when fortune smiled upon me, one of my first duties was the erection of a monument to my benefactor. It stands in front of the Hall and Library in Diamond Square, which I presented to Allegheny, and bears this inscription:

To Colonel James Anderson, Founder of Free Libraries in Western Pennsylvania. He opened his Library to working boys and upon Saturday afternoons acted as librarian, thus dedicating not only his books but himself to the noble work. This monument is erected in grateful remembrance by Andrew Carnegie, one of the “working boys” to whom were thus opened the precious treasures of knowledge and imagination through which youth may ascend.

Personal life

On April 22, 1887, Andrew Carnegie married Louise Whitfield at her family’s home in New York City in a private ceremony officiated by a pastor from the Church of the Divine Paternity, a Universalist church to which the Whitfields belonged. At the time of the marriage, Louise was 30; Carnegie was 51. Ten years later in 1897, Louise gave birth to the couple’s only child Margaret Carnegie Miller.

All the Best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

2 Comments

Pingback: Lessons Learned from Dr. Patrick N. Allitt’s Great Courses Class: The Industrial Revolution. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: Colonel Anderson and Books. – Lanre Dahunsi