The machines are coming! Winter is coming! Those are some of my favorite aphorisms of late; the COVID-19 pandemic is accelerating the fourth industrial revolution. The thing with history is that it does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. I have always been curious about the industrial revolution; why did it take place in Britain? Why did America eventually become the eventual pacesetter in that revolution? What are the similarities between the victorian inspired industrial revolution and the present day 4th industrial revolution? The role of industrialization in the world wars?

The great courses class answers a lot of these questions, with 36 Lectures in 18 hours

The Industrial Revolution Great Courses class covers the emergence of the Industrial Revolution in 18th century Britain and the spread of its inventions and ideas to the fledgling United States, seeking to show how and why this great modern transformation occurred.

From the steam engine to the horseless carriage, the rise of the factory to the role of immigrant labor, the course provides insight not only into the historical period but also into the birth of modern life and work as we know it.

The Lecturer

Professor Patrick N. Allitt was born in 1956 and raised in Mickleover, England. He attended John Port School in the Derbyshire village of Etwall and was an undergraduate at Hertford College, University of Oxford, from 1974 to 1977. He studied American History at the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned his Ph.D. in 1986. Between 1985 and 1988, he was a Henry Luce Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard Divinity School, where he specialized in American Religious History. Since then, he has been on the history faculty of Emory University, except for one year (1992–1993) as a fellow at the Princeton University Center for the Study of Religion. He was the director of Emory’s Center for Teaching and Curriculum from 2004 to 2009 and has been the Cahoon Family Professor of American History since 2009.

British Origin

- Britain was the first country to undertake industrialization. It began in the mid 18th century, by which time Britain had achieved political stability, acquired a colonial and commercial empire, founded banks and insurance systems, and discovered ways to increase its food output so that fewer farmers could feed more people than ever before.

- First in the cotton textile industry, then with improvements in coal mining, pottery manufacture, and iron smelting, new methods began to catch on, including the application of water and steam power to machinery, the concentration of large workforces in factories and mines, and the division of labor.

- The Industrial Revolution, which transformed the world over the past two and a half centuries, was the most profound and beneficial event in human history since the Neolithic Revolution—the discovery some 12,000 years ago that plants and animals could be domesticated.

In Britain, the development of political stability after 1689 made investors willing to risk their money on industrial ventures

Glorious Revolution,

These events of 1688–1689, known as the Glorious Revolution, created conditions of political stability that have endured right up to the present, making the constitutional monarchy of Britain one of the most durable in the world.

British Population Growth

- Population rose rapidly between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries. The population of Britain was about 5 million in 1700 and only half a million more by 1750. Then it took off; there were 8.3 million people by 1801 and 16.8 million by 1851.

The Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, or the (First) Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible.

Industrialization depends on the idea that tradition should not always constrain us and that careful thought can enable us to do what our ancestors never even attempted. In this sense, industrialization has immense antitraditional implications.

The nature of social change is that it produces winners and losers. Each time a technology is made obsolete, some people may lose their livelihoods or drop out of the workforce altogether.

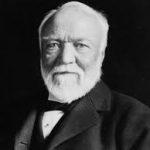

- The great iron and steel manufacturer Andrew Carnegie once said that capitalism was all about turning luxuries into necessities. In other words, new inventions that once caused a sensation gradually become familiar and feel normal, until we reach the point of wondering how we ever got along without them. Then, we forget how useful they are until we’re forced to do without them again.

The Agricultural Revolution

- British agriculture became increasingly productive in the century after 1700, freeing up thousands of people to leave the land and move into manufacturing work. A combination of factors made these improvements possible, including new forms of land tenure and use, enhanced crops, improvements in animal breeding, and innovations in farm machinery. Some historians call these processes, collectively, the Agricultural Revolution. Population was growing rapidly after 1750, but food production more than kept pace, so that the ancient specter of famine receded ever farther into the distance.

The Royal Shipyards

- The shipyards of the Royal Navy created the large-scale organization of work, materials, logistics, and complex construction that would be characteristic of later factory-era industrialization and pioneered many of these methods in a nation still using techniques that were slow, labor intensive, tradition bound, and based on organic materials.

- Shipyards pioneered the bulk ordering of raw materials (wood, rope, barrel hoops and slaves, and cannons) and refined logistics and materials flow. The industry also gave rise to ancillary businesses, an arrangement that would later be common in industrial towns.

The Textile Industry

- For centuries, Britain had a thriving domestic and export trade in woolen cloth. In the late 18th century, a group of entrepreneurs invented machines to spin thread and weave cotton cloth, then built some of the world’s first factories to house them.

- The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 enabled American planters to grow cotton in bulk, most of which was shipped to Liverpool. Key advancements realized by the textile industry included the gathering of workers into the same place to work under close supervision; the invention of machines that could work faster and more consistently than hand workers; the application of power sources to those machines; and the development of huge domestic and foreign markets.

The possibility of using women and children as textile workers coincided with the Napoleonic Wars (1790s–1815), when large numbers of men were in the armed services.

Coal Mining—Powering the Revolution

- The industrial Revolution ran on coal. Immense coalfields underlie parts of Britain, and coal had been mined and quarried to a small extent ever since pre-Roman times. Improvements in mining technology in the 18th century, however, along with rising demand, transformed coal mining into a large-scale capitalist enterprise. Coal fueled the steam engines that turned the textile machines, and it powered the furnaces that created large-scale iron and steel manufacturing.

Improved Transport

- Tramways – The World’s first railways

- First Bridge – Tanfield Arch (Causey Arch)

Iron—Coking and Puddling

- Until the late 18th, the use of iron was confined mainly to horseshoes, nails, knives, weapons, and cooking pots.

- The availability of inexpensive ferrous metals (iron and steel) was one of the necessary conditions for the Industrial Revolution. Iron is much more durable than wood; a wooden industrial machine would be vibrated or pounded to pieces after a year’s work, but one made of iron would last for decades. Like coal mining, the iron industry has origins stretching back well before 1750, and its transformation took place in gradual stages.

The Railway Revolution

A National Effort

- In Britain, each new railway line required an act of Parliament. The acts provided limited liability and created the right of eminent domain. Because Britain was already a densely settled country, the siting of lines meant cutting across lands owned by hundreds of individuals. Bribery of Members of Parliament, who owned estates the railways would cross, was widespread and contributed to the high cost of British railway building.

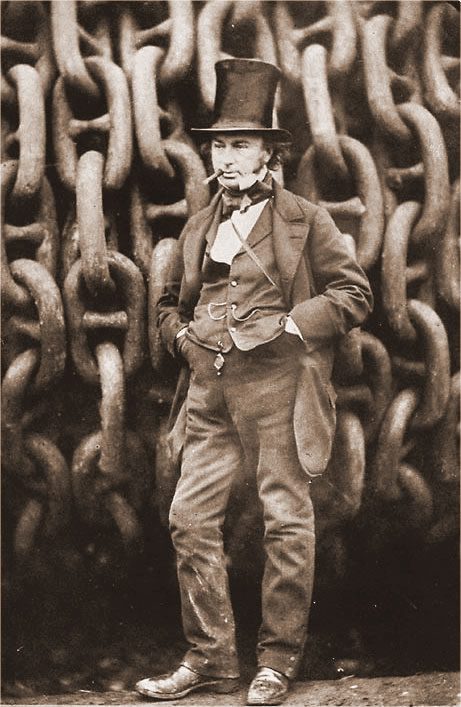

Isambard Kingdom Brunel

- Brunel used a seven-foot railway gauge for greater comfort and However, a seven-foot gauge made the line more costly to build, enforced shallower curves, and prevented interchangeability of rolling stock.

- Railways stimulated economic growth both directly and indirectly. Communication between cities was quicker and easier than ever before, as was bulk transport of low-value items, such as coal, iron ore, and cotton.

- Railways under construction were a major stimulus to the iron and steel business, contractors, brickworks, and mining. By 1850, all the largest companies on the London stock exchange were railways, and they were far more highly capitalized than even the biggest Manufacturers

New Management Challenges

- Stagecoach lines’ fears that railways would displace them were well-founded, but the demand for short term horse-drawn transport actually accelerated, and the number of horses and carriages in Britain continued to rise as cities grew and citizens’ wealth increased.

- Railways created a new class of managers, remote from their employers, who had to take responsibility for the safe working of the railways. Most industries until then operated all in one place, under the supervision of the owner or overseer, but railways, by their nature, were dispersed. Managers had to show the right blend of subordination and initiative to prevent crashes and to keep the system running smoothly and according to schedule.

- Companies also recognized the need for long-term worker loyalty and tried to make working for the railway a lifetime proposition with security and dignity. Railways built by private enterprise meant owners did not have to contend with bureaucratic national planning,

The Railway Bubble

- More railway lines were projected than were ever built, and some lasted only a few years before falling into bankruptcy. After the astonishing success of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, a great surge of enthusiasm in 1836–1837 led to a bubble, with some unwise overinvestment in railways by people who lacked the necessary detailed knowledge.

- The diversity of private ventures also led to the building of 13 separate London termini but no general exchange, which created severe transshipment problems and remained a weakness of the system into the 20th century.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel—Master Engineer

He was a Promethean figure, intellectually and technologically daring, who pushed new possibilities further than any of his contemporaries.

- In 1833, at age 27, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway and built it to a higher level of quality and comfort than any rival line.

- The Stephensons, Brunel, and the other great Victorian engineers were able to build accurate, efficient locomotives and steamships because they had access to something none of their predecessors had enjoyed—high-quality machine tools. Late-18th-century and early-19th-century craftsmen learned how to make more accurate and more durable lathes, stamps, taps, dies, and all the other devices essential for turning out precision machinery.

The Machine-Tool Makers

John “Longitude” Harrison

- A long tradition of skilled craftsmanship in metals contributed to the development of high-quality machinery. Among the preindustrial craftsmen, clock makers and watchmakers were the most skilled. The quest for accurate marine chronometers challenged a generation of clock makers, of whom the most distinguished was John “Longitude” Harrison (1693–1776).

Prizes

- The challenge of making a clock that accurate took most of Harrison’s lifetime. Harrison aimed to win a prize of £20,000, offered by the Admiralty in 1714. The prize was offered in the wake of a disaster at sea, in which an english fleet whose navigator had miscalculated their longitude foundered on the rocks; 2,000 men were lost.

The Worker’s-Eye View

The “De-Skilling” of Workers

- The shift to industrial work often entailed “de-skilling” of workers. The traditional sequence of apprentice, to journeyman, to master was displaced by a situation in which employees performed a single job. Many of these jobs, in mining, shipbuilding, and iron and steel working, required great physical strength, which gave advantage to younger men. Miners and shipyard workers sometimes worked in gangs of different ages, partly as a way of protecting their older members.

- While employers sought control over their workers, working people in many trades struggled to retain some sense of autonomy. Mine workers owned their own picks and shovels, for example, and paid to have them kept sharp by the blacksmith. Shoemakers had their own tools, as did coopers (barrel makers).

Separation of Work from Home Life

- Workers shared the middle-class ideal that the man should work and his wife should stay at home to look after the children. On farms, women had traditionally worked as long and as hard as their husbands, but after migration to the towns, the separation of work from home created a new ideal.

Workers’ Protections

- An obvious way for the workers to react to poor wages, job insecurity, and dangerous working conditions was by creating trade unions—strength in unity. However, fear of the French Revolution prompted Parliament to pass the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800, making it illegal for workers to conspire in this way.

Only “friendly societies” were allowed, in which workers paid weekly sums with the promise of sick pay or a decent burial if they died in a work accident.

Luddism

- One response was intimidation of employers by workers. Another response was Luddism, a violent, destructive protest against labor-saving machinery. Luddites were named for “Ned Ludd”, a semi-mythical figure, comparable to Robin Hood, who stood up for the poor by attacking symbols of their oppression. Luddism began during the economic crisis conditions of 1811–1812 in Nottinghamshire.

- Hosiery employers were using new looms and unskilled labor; the Nottingham workers responded by smashing the machines. Luddism then spread to northern areas, where hand workers were threatened with displacement by machinery. This panicked the government, which devoted huge resources to stamping out Luddism. Eventually, the movement was repressed.

Mercantilism

- In the 18th century, the prevailing economic theory was mercantilism, based on the idea of z zero-sum game: One Nation’s gain must be another nation’s loss. Therefore, according to the theory, a nation must bring in more gold and silver than it exported and try to keep as much trade as possible for itself.

- This theory motivated the acquisition and jealous preservation of colonies by Britain and other European powers. It justified high tarriffs, to make it difficult for other nations’ goods to sell in Britain, It inspired the notorious Navigation Acts, which mandated that all of Britain’s colonial trade must come via England and must be in British or British colonial ships.

Mercantilism presupposed that a nation’s strength required close political regulation of economic activities—a claim that the theorists of the industrial age were about to challenge.

American Pioneers—Whitney and Lowell

- The American Revolution coincided with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, but there were important differences between the two countries. Where Britain had little land and a large population, America had an immense quantity of land and a comparatively small population. Some of the Founding Fathers, including Thomas Jefferson, wanted to prevent America from following the British path because he thought of cities as centers of vice and moral decay.

The Entrepreneurial Americans

- In 1815, when the Napoleonic Wars ended, 95 percent of Americans made their living in farming or agriculture-related pursuits, whereas in Britain, that number had already fallen to about 30 percent. At the same time, however, an enterprising minority of Americans had begun to establish industries, especially in the northern states.

- The important difference between rural dwellers in Europe and America was that the Americans had a highly entrepreneurial outlook, were receptive to innovation, were politically active (nearly all white men had the vote by the 1820s), and thought of their farms in terms of businesses rather than subsistence.

- America had no feudal past and no peasants—these were middle-class citizens who were familiar with the idea of taking risks to make gains. Unlike the British, they were also highly mobile, willing to move for opportunities. Most had at least some education and were probably the most literate people in the world at that time.

Samuel Slater

- One approach to American industrialization was to bring British experts to the United States. Throughout the 18th century, Britain had passed laws to prevent the emigration of skilled craftsmen and technology. Hamilton actively supported industrial espionage and the acquisition of skilled workers from Britain. Jefferson was skeptical of the idea and called these workers “ephemeral pseudo-citizens.

- The most famous of these transplants was Samuel Slater, who built the first commercially successful spinning mills in the United States and became a millionaire industrialist. In England, he was nicknamed “Slater the Traitor,” but in the United States, he is known as the father of the American Industrial Revolution.

Why Europe Started Late

- Before about 1830, Europe lacked several of the characteristics that helped Britain pioneer the Industrial Revolution. First, it was swept by constant warfare. Second, it was politically fragmented, especially in Germany and Italy. Third, European banking and insurance systems were less well developed than those in Britain, prohibiting the growth of innovation and invention.

Werner von Siemens

- Siemens built the world’s first electrically powered elevator. He contributed to the development of X-rays, dynamos, and loudspeakers, and he bought the rights to develop Edison’s inventions in Germany. Siemens also encouraged the creation of high-quality technical schools in Germany for training new generations of technologists.

Increasing Industrial Output in Germany

- Between 1870 and 1900, Germany’s percentage of the world’s industrial output rose from 16 percent to 19 percent, while Britain’s fell from 32 percent to 18 percent. By World War I, Germany and the United States had both overtaken Britain. In 1870, the biggest British companies were still larger than the biggest German ones, but by 1900, the situation was reversed.

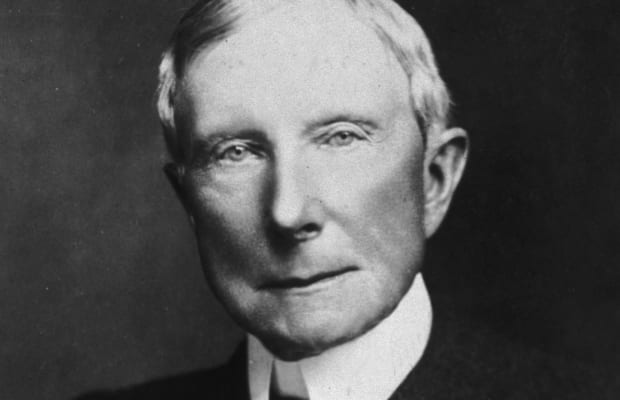

John D. Rockefeller

- Soon after the first oil strikes, John D. Rockefeller arrived from nearby Cleveland. He quickly realized that the most lucrative part of the business lay not in getting oil out of the ground but in refining and marketing it.

- By 1890, Rockefeller was probably the richest man in the world. He eventually became a large-scale philanthropist. He founded and donated millions to the University of Chicago, yet he refused to have any of its buildings named after him.

- He built Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Steel Company, which he sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901 for $303,450,000. It became the U.S. Steel Corporation. After selling Carnegie Steel, he surpassed John D. Rockefeller as the richest American for the next several years.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.