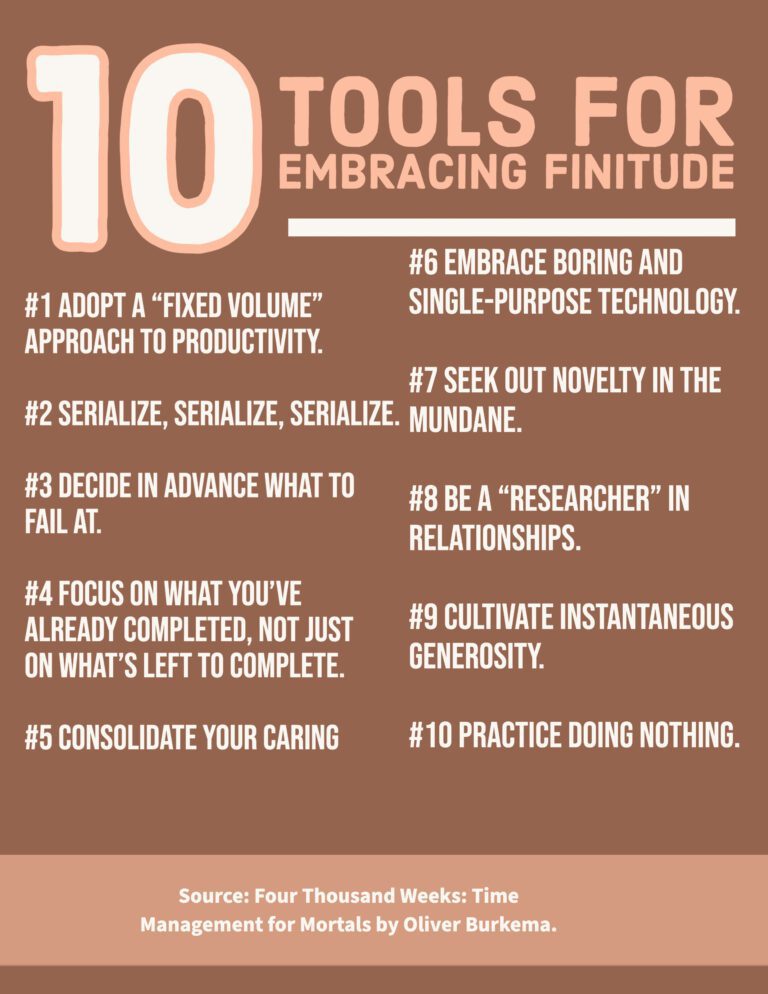

In his illuminating book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals British journalist Oliver Burkema highlighted ten tools for embracing the finitude of our time here on earth. In the book’s appendix, Burkema shared the following tools and strategies for embracing our mortality.

1. Adopt a “fixed volume” approach to productivity.

Much advice on getting things done implicitly promises that it’ll help you get everything important done—but that’s impossible, and struggling to get there will only make you busier. It’s better to begin from the assumption that tough choices are inevitable and to focus on making them consciously and well.

Keep Two to-do lists: Open and Closed

The open list is for everything that’s on your plate and will doubtless be nightmarishly long. Fortunately, it’s not your job to tackle it: instead, feed tasks from the open list to the closed one—that is, a list with a fixed number of entries, ten at most. The rule is that you can’t add a new task until one’s completed.

You’ll never get through all the tasks on the open list—but you were never going to in any case, and at least this way you’ll complete plenty of things you genuinely care about.

Establish Predetermined time boundaries for your daily work

To whatever extent your job situation permits, decide in advance how much time you’ll dedicate to work—you might resolve to start by 8:30 a.m., and finish no later than 5:30 p.m., say—then make all other time-related decisions in light of those predetermined limits.

2. Serialize, serialize, serialize.

Following the same logic, focus on one big project at a time (or at most, one work project and one nonwork project) and see it to completion before moving on to what’s next.

It’s alluring to try to alleviate the anxiety of having too many responsibilities or ambitions by getting started on them all at once, but you’ll make little progress that way; instead, train yourself to get incrementally better at tolerating that anxiety, by consciously postponing everything you possibly can, except for one thing. Soon, the satisfaction of completing important projects will make the anxiety seem worthwhile—and since you’ll be finishing more and more of them, you’ll have less to feel anxious about anyway.

3. Decide in advance what to fail at.

You’ll inevitably end up underachieving at something, simply because your time and energy are finite. But the great benefit of strategic underachievement—that is, nominating in advance whole areas of life in which you won’t expect excellence of yourself—is that you focus that time and energy more effectively. Nor will you be dismayed when you fail at what you’d planned to fail at all along.

To live this way is to replace the high-pressure quest for “work-life balance” with a conscious form of imbalance, backed by your confidence that the roles in which you’re underperforming right now will get their moment in the spotlight soon.

4. Focus on what you’ve already completed, not just on what’s left to complete.

Keep a “Done List”

It starts empty first thing in the morning, and which you then gradually fill with whatever you accomplish through the day. Each entry is another cheering reminder that you could, after all, have spent the day doing nothing remotely constructive—and look what you did instead!

5. Consolidate your caring

Social media is a giant machine for getting you to spend your time caring about the wrong things, but for the same reason, it’s also a machine for getting you to care about too many things, even if they’re each indisputably worthwhile.

Consciously pick your battles in charity, activism, and politics

To decide that your spare time, for the next couple of years, will be spent lobbying for prison reform and helping at a local food pantry—not because fires in the Amazon or the fate of refugees don’t matter, but because you understand that to make a difference, you must focus your finite capacity for care.

6. Embrace boring and single-purpose technology.

Digital distractions are so seductive because they seem to offer the chance of escape to a realm where painful human limitations don’t apply: you need never feel bored or constrained in your freedom of action, which isn’t the case when it comes to work that matters.

- You can combat this problem by making your devices as boring as possible—first by removing social media apps, even email if you dare, and then by switching the screen from color to grayscale.

- Choose devices with only one purpose, such as the Kindle e-reader, on which it’s tedious and awkward to do anything but read.

7. Seek out novelty in the mundane.

Pay more attention to every moment, however mundane: to find novelty not by doing radically different things but by plunging more deeply into the life you already have. Experience life with twice the usual intensity, and “your experience of life would be twice as full as it currently is”—and any period of life would be remembered as having lasted twice as long. Meditation helps here. But so does going on unplanned walks to see where they lead you, using a different route to get to work, taking up photography or birdwatching or nature drawing or journaling, playing “I Spy” with a child: anything that draws your attention more fully into what you’re doing in the present.

8. Be a “researcher” in relationships.

Curiosity is a stance well suited to the inherent unpredictability of life with others, because it can be satisfied by their behaving in ways you like or dislike—whereas the “stance of demanding a certain result is frustrated each time things fail to go your way.

Indeed, you could try taking this attitude toward everything, as the self-help writer Susan Jeffers suggests in her book Embracing Uncertainty. Not knowing what’s coming next—which is the situation you’re always in, with regard to the future—presents an ideal opportunity for choosing curiosity (wondering what might happen next) over worry (hoping that a certain specific thing will happen next, and fearing it might not) whenever you can.

9. Cultivate instantaneous generosity.

As proposed by meditation teacher Joseph Goldstein:

Whenever a generous impulse arises in your mind—to give money, check in on a friend, send an email praising someone’s work—act on the impulse right away, rather than putting it off until later. When we fail to act on such urges, it’s rarely out of mean-spiritedness, or because we have second thoughts about whether the prospective recipient deserves it.

10. Practice doing nothing.

I have discovered that all the unhappiness of men arises from one single fact, that they cannot stay quietly in their own chamber – Blaise Pascal

When it comes to the challenge of using your four thousand weeks well, the capacity to do nothing is indispensable, because if you can’t bear the discomfort of not acting, you’re far more likely to make poor choices with your time, simply to feel as if you’re acting—choices such as stressfully trying to hurry activities that won’t be rushed or feeling you ought to spend every moment being productive in the service of future goals, thereby postponing fulfillment to a time that never arrives.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.