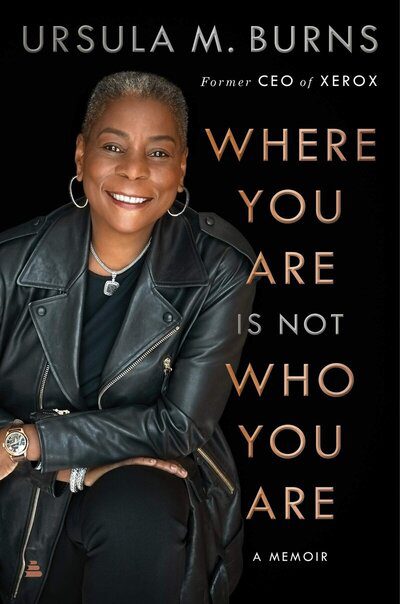

In 2009, Ursula became the first African American woman CEO of a Fortune 500 company when she was appointed as the Chief Executive Officer of the Xerox Corporation. In her memoir, Where You Are Is Not Who You Are, Ursula chronicles her story of growing up in poverty, being an outsider most of her life, her career trajectory, and the lessons learned leading a fortune 500 company as a black woman.

Burns writes about her journey from tenement housing on Manhattan’s Lower East Side to the highest echelons of the corporate world. She credits her success to her poor single Panamanian mother, Olga Racquel Burns—a licensed child-care provider whose highest annual income was $4,400—who set no limits on what her children could achieve. Ursula recounts her own dedication to education and hard work, and how she took advantage of the opportunities and social programs created by the Civil Rights and Women’s movements to pursue engineering at Polytechnic Institute of New York.

Favorite Takeaways: Where You Are Is Not Who You Are: A Memoir by Ursula Burns.

Life happens one day at a time, and only in the retelling does it come together into remarkable, exciting, or insightful stories. In other words, you live your life not knowing the end of the story, and retell it only as if you knew what the outcome would be.

“Being wildly overprepared answered the question that people had but didn’t ask when they first met me: “How the hell did she get here?”

“As a Black woman, I had to prove myself worthy of whatever position I was in because my coworkers would cut me no slack. I hadn’t slept my way up the chain. I wasn’t the recipient of preferential treatment. I wanted to make sure that the audience knew that I’d earned my position. To do that, I made sure they understood that I knew at least as much as anyone in the room. It was a defense mechanism against the assumption that I didn’t belong.”

Negative stereotype with an assumption of guilt.

The burden eased as I became more senior and certainly when I became CEO. But even in the most senior position where I could wield power and impact, some tension remained. I felt it when addressing the company or sitting in a conference room where everyone in that space either worked for me or wanted my position. I was conscious of looking different and being surrounded by people who wished I didn’t. It was a negative stereotype with an assumption of guilt.

There was nothing I could do about being Black or a woman, and I wouldn’t have changed it if I could. I liked being a novelty. It gave me a high profile among the Fortune 500 CEOs, and I used it to inspire women of all races.

The Machines are coming

Some analysts predict that at least 60 percent of the jobs of today will be gone or reconfigured over the next ten to twenty years, requiring workers to either be laid off or to learn new skills. And no one, as yet, has come up with a national policy or solution, though plenty of individuals and many different coalitions are working on it, including the Aspen Institute, MIT, and governments around the world.

America has lived through technology-driven unemployment transitions before, including the invention of the cotton gin and the introduction of robots in factories. But this transition is occurring faster than earlier ones. It is happening so quickly and so broadly that businesses and governments must act now to prepare for the future of a large number of people without useful work to do. If we don’t, we’re going to have revolt in the streets.

Some analysts predict that at least 60 percent of the jobs of today will be gone or reconfigured over the next ten to twenty years, requiring workers to either be laid off or to learn new skills.

On Poverty

Poverty has a color—or, more accurately, an absence of color. Everything seems to be sepia when you’re poor. Poverty has a persistent odor too, from the mounds of garbage the city rarely picks up, to the urine in the stairwells and elevators, to the decay in the century-old buildings. Our tenement apartment at Third Street and Avenue D in New York had all those trappings of poverty.

“My mother refused to have her children be defined by it. “Where you are is not who you are,” she told us time and again. I didn’t know what she was talking about.

Mothers Highest Income: $4,400

How did my mother raise three children on little more than pocket change? Her highest annual income, I discovered after her death, was $4,400. Yet she somehow paid the fee to send us all to parochial school instead of public school so my siblings and I could get the best and safest education possible.

Poverty has a pace

Poverty has a pace, and the sidewalks were crowded with people rushing around in a frantic fashion, people racing great distances to save $1 here or there or hurrying to stand in line for a handout.

Avid Reader

My sister and brother did most of their living outside, doing sports, hanging out with friends. I didn’t. Instead of going outside, I stayed home and read. I think it was my way of avoiding the world. Among my favorite books was a series of love stories written by Andrew “Greeley, a Roman Catholic priest. I read a lot of history books too, not scholarly books about the American Revolution, but books about people in history, like John Adams and Alexander Hamilton. I was an avid reader, and I consumed the books I took out from the nearby public library or that were given to me as presents.

Internships

I started interning the summer after my freshman year. HEOP hosted corporations on campus, and I was recruited for two summers by Western Electric Engineering Research Center in Princeton Junction, New Jersey. The whole idea of working and having to get work clothing was entirely foreign to me, as was mixing with the engineers at Western Electric who were much older than me. And I was one of the few female interns and one of the very few people of color. My world suddenly became much larger.

I also enjoyed getting a weekly salary for the first time, as my former jobs paid by the hour. The salary I was making as an intern was fairly good and went a long way toward bankrolling my next year in college. But the internship was much more than money. It showed me a completely different world from my day-to-day life on the Lower East Side of Manhattan—people who worked in a big company, people who drove cars to work, people who earned a significant amount of money. For the first time I realized that could be me.

Internship at Xerox

I thought I’d try something new at the end of my junior year and accepted an internship at Xerox. I had two more years before I would look for a permanent job, and an internship was a great way to look at a company and for the company to look at me. Xerox was very different from Western Electric. The people there were more engaging and curious about who I was, and they wanted me to come back to work for them.

At Western Electric, the internship was more about evaluating potential employees than about introducing them to the company. At Xerox, the interns spent a week in orientation in Leesburg, Virginia, where we were told the history of the company and xerography, the technology that made Xerox, Xerox. It was a different approach, and I liked it.

Armed with my master’s in mechanical engineering, I started working full-time for Xerox in 1981. I stayed for thirty-six years.

Mother’s favorite sayings:

- Leave behind more than you take away.

- Don’t let the world happen to you. You happen to the world.

- God doesn’t like ugly.

- Take care of each other.

- Don’t do anything that wouldn’t make your mother proud.

- Where you are is not who you are (and remember that when you’re rich and famous).

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.