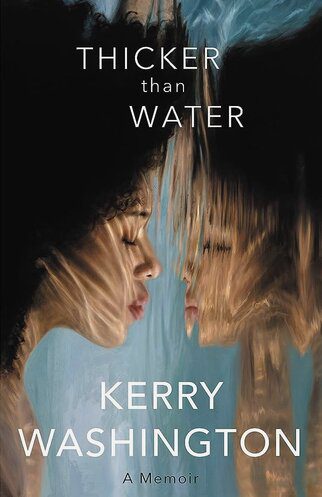

I fell in love with Kerry Washington’s character, Olivia Pope, in the American political thriller television series Scandals. Her performance won her the Image Award for Outstanding Actress in a Drama Series and other multiple award nominations, including Emmy Award and Golden Globe Award nomination. In Thicker than Water: A Memoir, Kerry Washington attempts to make sense of herself, her upbringing and her family dynamics.

I’ve written this account to more fully understand this truth, to affirm it, and to embrace it. This truth has given birth to a deeper compassion and love for my parents, and for myself. And I share it with you because I do not want to hide.

Kerry reveals how her parents did not reveal to her that she was conceived through artificial insemination until recently. She writes about her parent’s tumultuous marriage, being an only child, navigating the family secret and finding her place in the world.

Only Child

From the start I knew that I was wanted, and I knew that I was loved. Even as a small child I was told that it had taken my parents a long time to have me. And my mother’s devotion to me was undeniable, her dedication palpable, her sacrifices endless. When it came to the development of my mind, she gave me the world.

Learning Framework

My mother’s years as an educator, coupled with her own deep love of learning, provided a framework that made me both curious and determined to excel. It’s no wonder that those mother-daughter evenings spent standing in the long half-price ticket line in Times Square, ready to see whatever show held the best seats at the lowest prices, evolved into opportunities to pursue a life in the arts all my own. But if the learning had been born of my mother’s influence, the dreaming and believing came from a different source.

My mother’s years as an educator, coupled with her own deep love of learning, provided a framework that made me both curious and determined to excel.

Dad’s electric creativity

My mother’s disciplined intellectual curiosity lives in opposition to my dad’s electric creativity. Earl Washington loves to laugh and create and dream and tell stories. He’s a modern-day griot who lives in the realm of magical thinking—his, and now my, deep faith in the possibility of dreams coming true, living against all logic, despite the odds and regardless of the facts, is absolute. It defines him. And it makes him irresistible to most.

Magical Realism

So, my mother’s drive to educate me, mixed with my dad’s endless imagination, encoded within me the artist that I would become. Today, well-researched magical realism is my job. And I feel blessed to love what I do. But even before it was my occupational calling, the ability to live in my imagination was necessary for survival, because in the reality of my day-to-day interactions with my parents, there was an inexplicable cognitive dissonance that made it impossible to fully connect.

Cognitive Dissonance

I did not lack for food, clothing, shelter, or culture—or any number of nice things—but I longed for an authentic connection with my parents. Something was missing, something felt wrong. And as many children do, I thought that something was me. What’s wrong with me? I asked myself, Why can’t I connect? Because despite all of it—the magic of Fantasia and the Broadway shows and the hawks and the sharks—from an early age I knew that something stood between my parents and me, a moat filled with their whispered conversations and my unanswered questions.

“You were a long–wished for child. You were not easy to conceive.”

Coping Mechanism

So I was able to create a narrative to fill in the blanks so that I could have something that resembled a cohesive inner life. I found ways to soothe my loneliness, disappearing into books and watching movies and playing make-believe. Eventually, I found my way to the stage and to film sets—places where I could be with other human beings and we could laugh together and cry together and make eye contact and breathe and say difficult things and experience joy. And live in truth. I went to the imaginary, looking for some truth. And I found it there.

Love for Swimming

My parents’ love of water seemed to guide their relationship and be passed onto me, somehow; perhaps genetically transferred into my bones. Being in water, moving through water, has always felt more natural to me than walking on land. When I am in the water, I am at peace, and when I am submerged, between breaths, I feel most at home with myself, in my body. As a child, even when I hated my body, I loved being in the water. I remember going to my mother one day in my bathing suit and pointing out the protruding shape of my belly as a flaw I wanted to fix. She said, “Just hold in your tummy. That’s what everyone does.

So, on land, in my bathing suit, I learned to restrict my body, to hold my breath, and to pretend. But in the water, I could be free. I have always loved the ways in which water manipulates sound. The way noise races across the surface, amplifying sound for miles, and then the muffled distance created by being underwater. This so often feels like an escape to me because the world gets quieter, my heartbeat grows louder, and my thoughts and feelings become precise, clear. When I’m stressed, swimming allows me a safe route out of myself, helping me to escape my thoughts and then return to a calmer, more centered version of me.

“On land, my instructions had been to remain small. But in water I was discovering a different part of myself. And I was learning to bring all of me into this particular effort.”

Playing an Illusory Role

When people ask me if I am the first actor in my family, I often joke that I am just the first to get paid for it. There are no other professional performing artists in our family tree that I know of, but we—my mom, my dad, and me—are a family of performers. Each of us has spent a lifetime playing a role vital to our shared narrative. My role in our performance came naturally because I was born into its twists and turns and draped in its masks and costumes. We three were the picture-perfect presentation of ourselves as we wanted to be perceived not only by the outside world, but by each other. We were a fairy-tale portrait of success. And this was the only show I knew—we performed it all day long, and for years. This script was how we tried to avoid pain, messiness, and discomfort.

The thing about an illusion is that, unless you are the magician, you don’t always see the trick when you are inside of it

The thing about an illusion is that, unless you are the magician, you don’t always see the trick when you are inside of it. My dad and mom were the magician and his assistant, and I was the audience member who had been invited onto the stage to be cut in half. I had no window into the secrets of how the trick had been performed, but I smiled and waved and received the applause in any case, knowing that without me, their act was incomplete. So, we dressed our part and performed our fairy tale, but like a princess hidden away in Jamie Towers, I knew that there was more to the story that I had yet to discover, more to my life that had yet to unfold.”

We were a family that colored inside the lines. We were innovators and entrepreneurs, but we were not rule breakers. We were the family that voted for barbed wire around our precious pool and called security when those boys dove into the deep end in the middle of the night. We desperately wanted to control the chaos that threatened our sense of safety. We would do almost anything to protect the illusion of our perfection.

Each of us has spent a lifetime playing a role vital to our shared narrative. My role in our performance came naturally because I was born into its twists and turns and draped in its masks and costumes.

Kerry’s parents were always fighting, and as a coping mechanism, she learned to people-please. She was supposed to deliver them happiness and was holding their marriage together. She writes:

There was yelling and crying, but only when they thought I was asleep. The next morning, they’d smile and pretend all was fine.… So, I, too, learned to smile, to cover for them, to pretend—to resist the call to see what was really going on. I learned to be someone else early on, my people-pleasing skills honed on those mornings when nothing was deemed amiss. I learned to keep my parents happy so that I would be safe. But something was still off. And I blamed myself.

From what I remember, most of the fights were about money, and about the fact that neither of my parents felt like they were in the marriage they wanted to be in, or more precisely, that neither was married to the person they wanted to be married to. They argued about my dad’s spending versus my mother’s thriftiness; my dad’s failures to earn versus my mother’s failure of ambition; my dad’s regular absences versus my mother’s obsession with me.

They both harbored deep disappointment over what their lives had become—my mother was disappointed in my dad, and my dad was disappointed in the marriage. I developed a sense that I was the only thing keeping them together, or that I had to try to be. I was supposed to deliver them to happiness, to avoid triggering in them any emotion even close to disappointment. So, when they fought, I took it as my failure, and felt like it was my job to fix it.

Magical thinking

Like a lot of families, the magic trick was in the pretending. We pretended to ourselves, to each other, and to the outside world that our family was not suffering the pain of life’s disappointments. We were fine—but I learned a long time ago that FINE can be an acronym for fucked-up, insecure, neurotic, and emotional.

I learned a long time ago that FINE can be an acronym for fucked-up, insecure, neurotic, and emotional.

Comments are closed.