People who are suffering from trauma don’t need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, “I’m sorry” or “This must really be hard for you” or “Can I bring you a pot roast?” Don’t say, “You should hear what happened to me” or “Here’s what I would do if I were you.” And don’t say, “This is really bringing me down.”

The Ring Theory is a concept developed by clinical psychologist Susan Silk and her friend arbitrator Barry Goldman. They suggest an approach that helps with not saying the wrong things when trying to support someone dealing with a crisis or in a stressful situation. They site a perfect example of such an unintended insensitive remark in their article:

When Susan had breast cancer, we heard a lot of lame remarks, but our favorite came from one of Susan’s colleagues. She wanted, she needed, to visit Susan after the surgery, but Susan didn’t feel like having visitors, and she said so. Her colleague’s response? “This isn’t just about you.”

The Ring Theory:

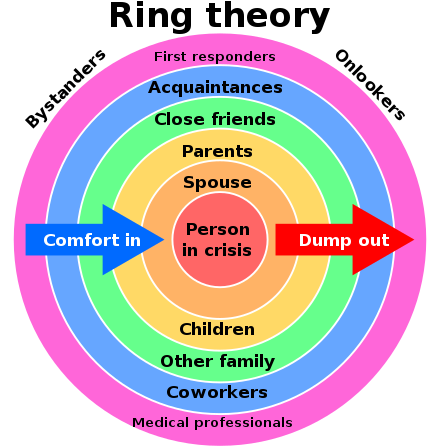

- Draw a circle. This is the center ring. In it, put the name of the person at the center of the current trauma.

- Now draw a larger circle around the first one. In that ring, put the name of the person next closest to the trauma.

- Repeat the process as many times as you need to. In each larger ring put the next closest people. Parents and children before more distant relatives. Intimate friends in smaller rings, less intimate friends in larger ones. When you are done you have a Kvetching Order.

The Rules:

- The person in the center ring can say anything she wants to anyone, anywhere. She can kvetch and complain and whine and moan and curse the heavens and say, “Life is unfair” and “Why me?” That’s the one payoff for being in the center ring. Everyone else can say those things too, but only to people in larger rings.

- When you are talking to a person in a ring smaller than yours, someone closer to the center of the crisis, the goal is to help. Listening is often more helpful than talking. But if you’re going to open your mouth, ask yourself if what you are about to say is likely to provide comfort and support. If it isn’t, don’t say it. Don’t, for example, give advice.

- People who are suffering from trauma don’t need advice. They need comfort and support. So say, “I’m sorry” or “This must really be hard for you” or “Can I bring you a pot roast?” Don’t say, “You should hear what happened to me” or “Here’s what I would do if I were you.” And don’t say, “This is really bringing me down.”

People who are suffering from trauma don’t need advice. They need comfort and support.

- If you want to scream or cry or complain, if you want to tell someone how shocked you are or how icky you feel, or whine about how it reminds you of all the terrible things that have happened to you lately, that’s fine. It’s a perfectly normal response. Just do it to someone in a bigger ring.

- Complaining to someone in a smaller ring than yours doesn’t do either of you any good. On the other hand, being supportive to her principal caregiver may be the best thing you can do for the patient.

Remember, you can say whatever you want if you just wait until you’re talking to someone in a larger ring than yours. And don’t worry. You’ll get your turn in the center ring. You can count on that.

The Ring Theory was first developed in 2013 by psychologist Susan Silk and her friend Barry Goldman. It helps people understand what to do in times of crisis. Picture a small circle, with a number of concentric circles around it. If the crisis is happening to you, you’re in the very center circle. The farther away you are from the center of the crisis, the farther out you sit in the rings.

In Silk and Goldman’s Ring Theory, grief (or complaints, anger, frustration, or as Silk calls it, “kvetching”) flows out from the center of the ring, whereas comfort—and only comfort—flows back in toward the center. This doesn’t just apply to grief; this theory can be applied to any crisis, whether that’s death, trauma, illness, injury, miscarriage, or divorce.

Understanding your role in any crisis will make you more comfortable setting the boundaries you need to keep yourself safe and healthy and should help you to be more understanding when someone in the center of the ring sets a boundary when you’re in an outer circle.

“Grief flows out, comfort flows in.”

Grief is a deeply tough emotion to deal with, and it can be made more challenging when one has to deal with the primarily unintended insensitive statements by others when one is dealing with a crisis, traumatic experience or stressful situation. I have had my share of grief situations in the last five years, from losing my mum to cancer to being laid off from a gig and a marital breakup. Every grief situation is different, but the insensitive remarks from others are one of the constants in all these situations. Platitudes such as “at least she was sick,” “I thought you’ve already moved on,” “everything happens for a reason”, “They’re in a better place now”, or “This too shall pass.” Most of these statements are kind of true, but that is not what the grieving wants to hear in the moment; statements. It’s been a rollercoaster navigating the multiple griefs I have had to deal with in the past five years, but I have learnt more about myself than in the previous 30 years.

Grief is a universal emotion that we all have to deal with, and it is not an emotion that most of us have the skill set to navigate. We make these statements not to cause more pain but because we do not know better or how deeply it hurts. A tool like the “Ring Theory” has been beneficial when dealing with grief with others. As author and podcaster, Tim Ferris often says, “Let’s try and be kinder than necessary.”

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.