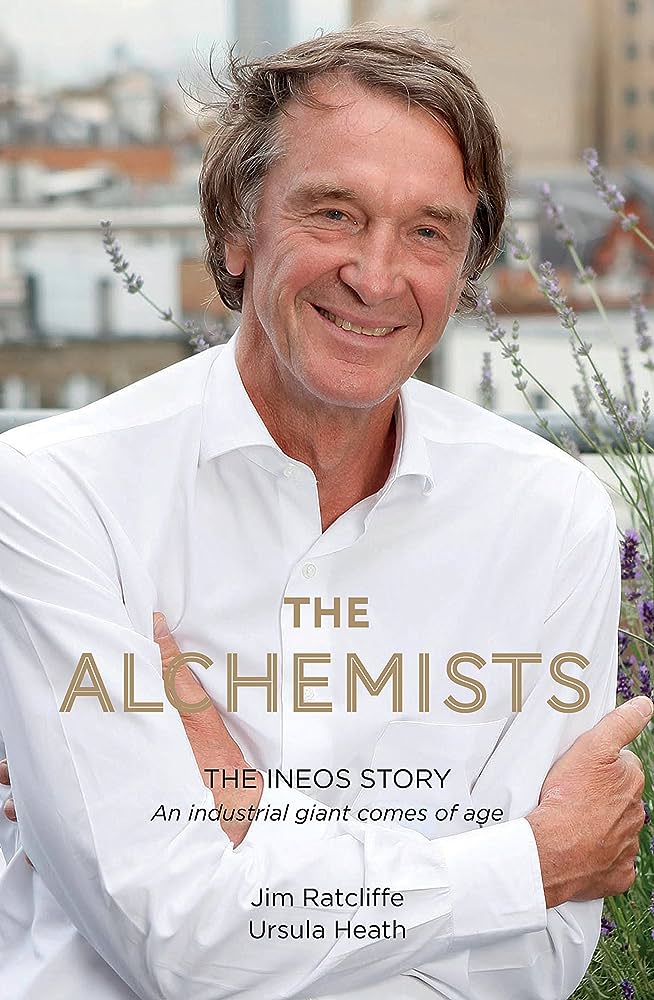

The Alchemists: The INEOS Story – An industrial giant comes of age is an autobiographical account of how British billionaire, chemical engineer and businessman Jim Ratcliffe built INEOS from a single site in Antwerp to the fourth-largest chemical company in the world and Britain’s largest private company. According to Forbes, Ratcliffe is the 77th wealthiest person in the world and the second richest Briton.

The Alchemist – About the rise of an unassuming and perhaps unlikely team with a canny combination of vision, intelligence, integrity, humility and steady competence in the face of recurring high stakes. A team that, together, created a lean, entrepreneurial, expanding business quite unlike any of its kind.

From a single site in Antwerp bought for £84 million and employing just 400 people, the company has grown exponentially since it was formed in May 1998. It is now a multinational giant, with 20,000 employees at over 100 sites in twenty-two countries across Europe, Asia and North America. By 2018, the company comprised thirty-two separate business units (including joint ventures), eighteen of which had an annual turnover of €1 billion or more – substantial enterprises in their own right. The rise in INEOS’s profitability has been similarly exceptional. Today, profits are just shy of $7 billion.

INEOS

The INEOS family of companies provides the chemical building blocks for everyday life. It purifies 90 per cent of the UK’s drinking water, supplies the raw materials to make everything from LEGO to medical equipment, develops specialist materials for future technologies, and touches almost everything else in between, on an international scale.

Modest Beginning

INEOS had a relatively modest beginning. Founder Jim Ratcliffe was a chemical engineer by training, who had fallen by fortunate accident into finance then venture capitalism in the early 1990s. Having become restless in his deal-making role at US firm Advent International, he was eager to manage one of the business investments he brokered long-term. Aged thirty-nine, during his fourth year at Advent, he spotted a suitable opportunity: a speciality chemical business BP had listed for sale at £37 million.

Putting a personal contribution of £140,000 into the deal, and risking everything he and his young family owned, Jim pursued plans to buy the business. Armed with a chemical engineer’s training, a London Business School MBA and a natural sense of profit potential, with an as-yet-untested risk orientation, he worked alongside then business partner and mentor John Hollowood, backed by Advent, his employer.

Meeting Business Partners

During the deal, Jim met Andy Currie, then working for BP, who was a fellow northern grammar-school boy with disarming business nous. The two would become close friends and lifelong business partners and, just two years later, would float the newly formed company, named Inspec – International Specialty Chemicals – at a value of £164 million.

In 1998, after acquiring Shell Fine Chemicals and other assets, Jim bought a significant petrochemicals plant in Antwerp from BP and, in the process, sold the balance of the Inspec business to British chemical company Laporte. On 5 May that year, he created a new company to hold the Antwerp plant, which was named INEOS and would lay the foundation for his business future. Two years after its auspicious birth, INEOS’s winning leadership trio was complete with the addition of John Reece, joining from leading accountants Price Waterhouse, as the INEOS numbers magnate and a perfect complement to the team.

INEOS trio’s business methodology

Turn loss-making acquisitions into profitable ones, and increase margins in those businesses that are already making money.

INEOS Principles

With Jim at the helm as company chief, John Reece as the master of numbers and Andy Currie heading up operations, the three-way partnership has rooted itself in a doctrine of six enduring principles, which guide the process of assessing, acquiring, rewiring and running their every venture. These ‘toolkit’ principles

- FIND orphaned or unwanted assets. (The success of a deal is in finding the right raw material to work with.)

- FOCUS on the fine detail of financial numbers. (Rigorous accounting sounds logical and essential, though the forensic levels applied by John Reece and his finance colleagues are rare.)

- FIXED costs management. (Tightly control all the variables you can, to create a lean and resilient outfit.)

- FEDERATED business model. (Accountability and responsibility in an organisation nurtures new ideas and bespoke efficiencies.)

- FOOTPRINT maximisation. (In the chemicals industry, maximising capacity – debottlenecking – is fundamental to efficiency and profitability.)

- FIVE years to double EBITDA. (A bold baseline aim to double Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation serves to bring into the family only the most promising of offerings – and drives visionary management with challenge.)

Work Hard Play Hard – Endurance Sport

As a youngster, as soon as he got back from school, he would do his homework and then rush outside to kick a ball around no matter what the weather. As he got older, his appetite for regular exercise grew – a 10-kilometre run every morning became part of his daily routine. Much later, curiosity as to his mental and physical capabilities – and no shortage of self-discipline – evolved into a penchant for endurance sport, as he built up from multiple marathons to ultramarathons, cycling trips to Tour de Franceesque feats, and, even at the age of sixty-five, an Iron Man triathlon, recognised as one of the toughest endurance events in the World. Formerly top of geography class at school, for Jim, this endurance drive is melded with a love of adventure and travel – a united desire to explore the world and his own limits. It is this passion that equally characterises and defines his unique management style.

Mentor – Tim Beecham

His grades were strong for the most part, winning As in cost accounting and economics, though he barely limped through office management with a mediocre C.

His real education, though, was through Tim, Beecham’s top accountant, who took Jim under his wing. It was here Jim learned the core of accountancy, where the cash book is king. The lifeline of a business was tracked through this simple system; on one side, the system records cash received, including accounts receivable and cash sales, and on the other, it records cash paid out such as accounts payable and expenses. The balance sheet, the profit and loss statement, and the statement of cash flows charted the pulse of a business, and were learned with intensive scrutiny.

From Tim, Jim learned the fundamental tools which would go on to underlie his phenomenal success with INEOS – the management of variable and fixed manufacturing costs, labour costs and sales and overheads. A fully fledged accountant with a chemical engineer’s training, after four years at Beecham, Jim had mastered a rare mix of skills.

Recommendation – Mysterious Supporter – Someone is always Watching

In 1987, fully settled and thriving in his role, Jim took a not-unexpected phone call from a head hunter. It was an American venture capital firm called Advent International, looking for someone to run its chemical and materials portfolio in London and worldwide. Jim had been recommended by a mysterious supporter, and the opportunity was too good to miss.

Only several years later did Jim discover that the head hunter who had tipped off Advent to recruit him was, in fact, Dr Norman Wooding, then deputy chairman of Courtaulds. ‘Isn’t that outrageous?!’ Jim laughed.

One should, if one can, try to maximise the number of days that are unforgettable.

Risk Remortgaging House

Of the individuals involved, John Hollowood invested £250,000, with Andy Currie adding an extra £30,000. But Jim’s was the biggest gamble. He staked every penny he owned, even remortgaging his family home to raise £140,000; ‘I put all my chips on it. So if that had gone down, I’d have been in a mess. But those were the old-fashioned days of venture capital.’ The venture was a bold one, and almost a disaster. On Wednesday 16 September 1992, ‘Black Wednesday’ as it is now known, the Bank of Scotland, the primary lender on the deal, called to back out of its commitment. The financial markets were unravelling.

Naming INEOS

The day of 5 May 1998 marked the minting of Jim’s new company, exactly three years to the day since his initial acquisition of Antwerp by Inspec. The new enterprise needed a name, however, as the lawyers called to remind Jim just hours before the deal drew to a close. Rushing to the local library, he brought a Latin and a Greek dictionary back to his family home in the New Forest and pored over words with his young sons Sam and George. After the boys had exhausted all the rude words, a more fitting name was suggested – INEOS, stemming from one Latin and two Greek roots. ‘Ineo’ is Latin for a new beginning; ‘Eos’ the Greek goddess of dawn; while ‘neos’ means something new and innovative – together heralding the ‘dawn of something new and innovative’. Conveniently, it was also an acronym of ‘In Ethylene Oxide and Specialities’, a rather more pragmatic name derived from the main products of Jim’s Antwerp plant and his portfolio of speciality chemicals companies.

Competitive Advantage

INEOS did what it always does when it comes to transforming this batch of troubled businesses – it bought new assets, closed old ones and stripped out layers of fixed costs. ‘There’s no rocket science here – we’re not super geniuses compared to the rest of the industry,’ declared Andy. ‘It’s just that we have a particular technique which is impossible for the big guys to copy. If you start big and try to shrink down, it won’t work.’ Growth in the early days was not simply made through acquisitions; a lot of investment was organic, made in existing plants.

What did make the company unique, at least in the eyes of the investors, was that it always used debt rather than equity to fund its deals; the management team continued to own 100 per cent of the company, despite making such a series of large acquisitions. This raised the level of risk for them, but assured lenders that they were fully accountable leaders.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.