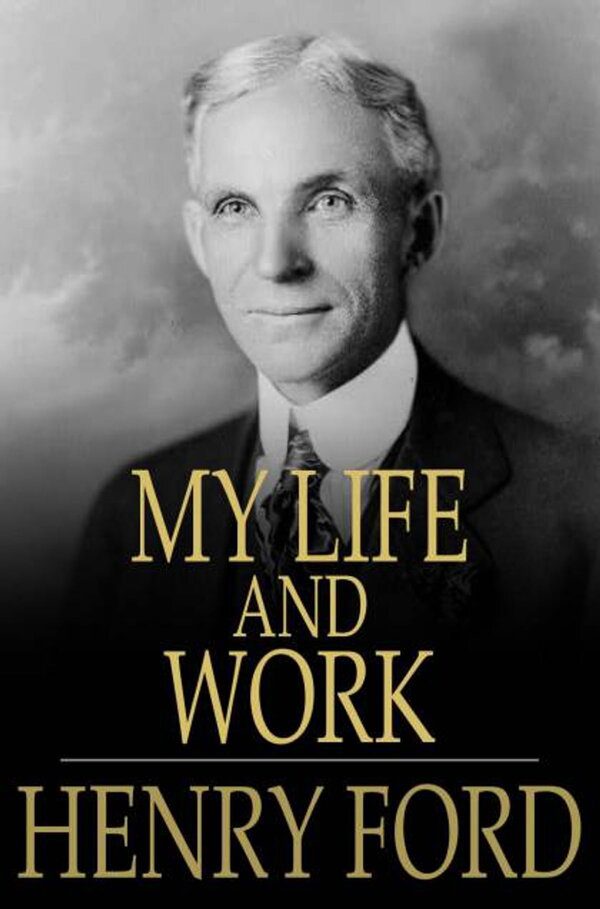

In My Life And Work, American industrialist, founder of the Ford Motor Company, Henry Ford highlights his business and life philosophies. He chronicles his journey of founding the Ford Motor Company, developing the assembly line technique of mass production, introducing the minimum wage, reducing working hours, the five-day work week, and producing the first automobile (Model T) that the middle class could afford. Ford’s autobiography is a great read and a good historical book on running a business during the world war and producing a product for the masses.

As of April 2022 Ford has a market cap of $60.80 Billion and the world’s 252th most valuable company by market cap.

Favourite Takeaways: My Life And Work by Henry Ford.

On Ideas

Most of the present acute troubles of the world arise out of taking on new ideas without first carefully investigating to discover if they are good ideas. An idea is not necessarily good because it is old, or necessarily bad because it is new, but if an old idea works, then the weight of the evidence is all in its favor. Ideas are of themselves extraordinarily valuable, but an idea is just an idea. Almost any one can think up an idea. The thing that counts is developing it into a practical product.

Almost any one can think up an idea. The thing that counts is developing it into a practical product.

Honest Effort

The natural thing to do is to work—to recognize that prosperity and happiness can be obtained only through honest effort. Human ills flow largely from attempting to escape from this natural course. I have no suggestion which goes beyond accepting in its fullest this principle of nature.

Common Sense

All that we have done comes as the result of a certain insistence that since we must work it is better to work intelligently and forehandedly; that the better we do our work the better off we shall be. All of which I conceive to be merely elemental common sense.

A man ought to be able to live on a scale commensurate with the service that he renders

Be of Service

Being greedy for money is the surest way not to get it, but when one serves for the sake of service—for the satisfaction of doing that which one believes to be right—then money abundantly takes care of itself. Money comes naturally as the result of service. And it is absolutely necessary to have money. But we do not want to forget that the end of money is not ease but the opportunity to perform more service.

The Product is the Key

People seem to think that the big thing is the factory or the store or the financial backing or the management. The big thing is the product, and any hurry in getting into fabrication before designs are completed is just so much waste time.

I spent twelve years before I had a Model T—which is what is known to-day as the Ford car—that suited me. We did not attempt to go into real production until we had a real product. That product has not been essentially changed.

The Ford company is erected based on the performance of service.The principles of that service are these:

1. An absence of fear of the future and of veneration for the past.

One who fears the future, who fears failure, limits his activities. Failure is only the opportunity more intelligently to begin again. There is no disgrace in honest failure; there is disgrace in fearing to fail. What is past is useful only as it suggests ways and means for progress.

2. A disregard of competition.

Whoever does a thing best ought to be the one to do it. It is criminal to try to get business away from another man—criminal because one is then trying to lower for personal gain the condition of one’s fellow man—to rule by force instead of by intelligence.

3. The putting of service before profit.

Without a profit, business cannot extend. There is nothing inherently wrong about making a profit. Well-conducted business enterprise cannot fail to return a profit, but profit must and inevitably will come as a reward for good service. It cannot be the basis—it must be the result of service.

4. Manufacturing is not buying low and selling high.

It is the process of buying materials fairly and, with the smallest possible addition of cost, transforming those materials into a consumable product and giving it to the consumer. Gambling, speculating, and sharp dealing, tend only to clog this progression.

Given a good idea to start with, it is better to concentrate on perfecting it than to hunt around for a new idea. One idea at a time is about as much as any one can handle.

The Origin Story of Ford

There was too much hard hand labour on our own and all other farms of the time. Even when very young I suspected that much might somehow be done in a better way. That is what took me into mechanics—although my mother always said that I was born a mechanic. I had a kind of workshop with odds and ends of metal for tools before I had anything else. In those days we did not have the toys of to-day; what we had were home made. My toys were all tools— they still are! And every fragment of machinery was a treasure.

The Defining Moments at 12

The biggest event of those early years was meeting with a road engine about eight miles out of Detroit one day when we were driving to town. I was then twelve years old.

The Art of Tinkering

Often I took a broken watch and tried to put it together. When I was thirteen I managed for the first time to put a watch together so that it would keep time. By the time I was fifteen I could do almost anything in watch repairing—although my tools were of the crudest.

There is an immense amount to be learned simply by tinkering with things. It is not possible to learn from books how everything is made—and a real mechanic ought to know how nearly everything is made. Machines are to a mechanic what books are to a writer. He gets ideas from them, and if he has any brains he will apply those ideas.

Machines are to a mechanic what books are to a writer. He gets ideas from them, and if he has any brains he will apply those ideas.

Be Weary of Experts

All the wise people demonstrated conclusively that the engine could not compete with steam. They never thought that it might carve out a career for itself. That is the way with wise people—they are so wise and practical that they always know to a dot just why something cannot be done; they always know the limitations. That is why I never employ an expert in full bloom. If ever I wanted to kill opposition by unfair means I would endow the opposition with experts. They would have so much good advice that I could be sure they would do little work.

I read everything I could find, but the greatest knowledge came from the work. A gas engine is a mysterious sort of thing—it will not always go the way it should. You can imagine how those first engines acted!

The year from 1902 until the formation of the Ford Motor Company was practically one of investigation. In my little one- room brick shop I worked on the development of a four- cylinder motor and on the outside I tried to find out what business really was and whether it needed to be quite so selfish a scramble for money as it seemed to be from my first short experience.

Built 25 automobile

From the period of the first car, which I have described, until the formation of my present company I built in all about twenty-five cars, of which nineteen or twenty were built with the Detroit Automobile Company. The automobile had passed from the initial stage where the fact that it could run at all was enough, to the stage where it had to show speed.

Function of Money

Money is not worth a particular amount. As money it is not worth anything, for it will do nothing of itself. The only use of money is to buy tools to work with or the product of tools. Therefore money is worth what it will help you to produce or buy and no more.

Money as an engine of production

If a man thinks that his money will earn 5 per cent, or 6 per cent, he ought to place it where he can get that return, but money placed in a business is not a charge on the business—or, rather, should not be. It ceases to be money and becomes, or should become, an engine of production, and it is therefore worth what it produces—and not a fixed sum according to some scale that has no bearing upon the particular business in which the money has been placed. Any return should come after it has produced, not before.

Don’t Settle

And also I noticed a tendency among many men in business to feel that their lot was hard—they worked against a day when they might retire and live on an income—get out of the strife. Life to them was a bat- tle to be ended as soon as possible. That was another point I could not understand, for as I reasoned, life is not a battle except with our own tendency to sag with the down pull of “getting settled.” If to petrify is success all one has to do is to humour the lazy side of the mind but if to grow is success, then one must wake up anew every morning and keep awake all day.

Business men go down with their businesses because they like the old way so well they cannot bring them- selves to change.

Fear of Public Opinion

There is also the great fear of being thought a fool. So many men are afraid of being considered fools. I grant that public opinion is a powerful police influence for those who need it. Perhaps it is true that the majority of men need the restraint of public opinion. Public opinion may keep a man better than he would otherwise be—if not better morally, at least better as far as his social desirability is concerned. But it is not a bad thing to be a fool for righteousness’ sake. The best of it is that such fools usually live long enough to prove that they were not fools—or the work they have begun lives long enough to prove they were not foolish.

Lessons Learned in business

(1) That finance is given a place ahead of work and therefore tends to kill the work and destroy the fundamental of service.

(2) That thinking first of money instead of work brings on fear of failure and this fear blocks every avenue of business—it makes a man afraid of competition, of changing his methods, or of doing anything which might change his condition

(3) That the way is clear for any one who thinks first of service—of doing the work in the best possible way.

Asking people what they want

Ask a hundred people how they want a particular article made. About eighty will not know; they will leave it to you. Fifteen will think that they must say something, while five will really have preferences and reasons. The ninety-five, made up of those who do not know and admit it and the fifteen who do not know but do not admit it, constitute the real market for any product.

The five who want something special may or may not be able to pay the price for special work. If they have the price, they can get the work, but they constitute a special and limited market. Of the ninety-five perhaps ten or fifteen will pay a price for quality. Of those remaining, a number will buy solely on price and without regard to quality.

Their numbers are thinning with each day. Buyers are learning how to buy. The majority will consider quality and buy the biggest dollar’s worth of quality. If, therefore, you discover what will give this 95 per cent. of people the best all-round service and then arrange to manufacture at the very highest quality and sell at the very lowest price, you will be meeting a demand which is so large that it may be called universal.

Bet on yourself

If I had followed the general opinion of my associates I should have kept the business about as it was, put our funds into a fine administration building, tried to make bargains with such competitors as seemed too active, made new designs from time to time to catch the fancy of the public, and generally have passed on into the position of a quiet, respectable citizen with a quiet, respectable business.

No Hiring of Experts

As I have said, we do not hire experts—neither do we hire men on past experiences or for any position other than the lowest. Since we do not take a man on his past history, we do not refuse him because of his past history. I never met a man who was thoroughly bad. There is always some good in him—if he gets a chance. That is the reason we do not care in the least about a man’s antecedents—we do not hire a man’s history, we hire the man.

You go as far as your hardwork

Some men will work hard but they do not possess the capacity to think and especially to think quickly. Such men get as far as their ability de- serves. A man may, by his industry, deserve advancement, but it cannot be possibly given him unless he also has a certain element of leadership. This is not a dream world we are living in.

Everything can always be done better than it is being done.

Comments are closed.