The thing is, it’s very easy to be different, but very difficult to be better.—JONY IVE

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple as CEO, he developed a partnership with British designer Jony Ive. Their collaboration produced some of the most iconic Apple products such as the iMac, iPod, iPhone and iPad. Jobs referred to Ive as his soul mate. The products revamped Apple to become a highly value company and venturing into different industries. In the process; Ive won various design awards, and got knighted by the Queen.

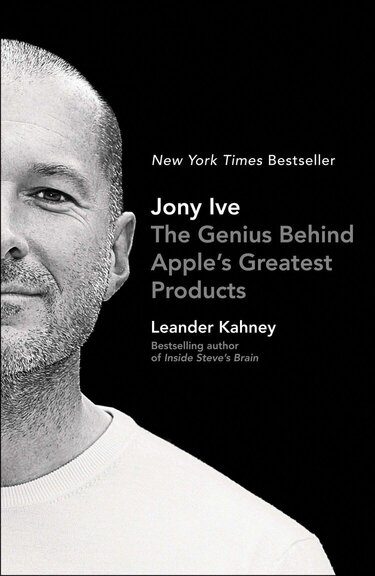

Technology author Leander Kahney writes about British-American industrial and product designer Jony Ive, who developed a very tight relationship with late CEO of Apple, Steve Jobs. Born in London, Ive rose to become Chief Design Officer (CDO) of Apple Inc.

Growing Up

Ive was born on February 27, 1967 in London. Jony Ive’s childhood circumstances were comfortable but modest. His father, Michael John Ive, was a silversmith, his mother, Pamela Mary Ive, a psychotherapist. They had a second child, daughter Alison, two years after their son’s birth.

Dyslexia

Jony attended Chingford Foundation School, later to be the alma mater of David Beckham, the famous soccer star (Beckham attended eight years after Jony). While at school, Jony was diagnosed with the learning disability dyslexia (a condition he shared with a fellow left-brained colleague, Steve Jobs).

Curiosity and Fathers Influence

As a young boy, Jony exhibited a curiosity about the workings of things. He became fascinated by how objects were put together, carefully dismantling radios and cassette recorders, intrigued with how they were assembled, how the pieces fit. Though he tried to put the equipment back together again, he didn’t always succeed.

Mike Ive encouraged his son’s interest, constantly engaging the youngster in conversations about design. Although Jony didn’t always see the larger context implied by his playthings, his father nurtured an engagement with design throughout Jony’s childhood.

Mike helped write the mandatory curriculum that became the blueprint for all UK schools, as England and Wales became the first countries in the world to make design technology education available for all children between the ages of five and sixteen.

The Design Story

In his slide presentations, the older Ive described the act of “drawing and sketching, talking and discussing” as critical in the creative process and advocated risk taking and a conscious acceptance of the notion that designers may not “know it all.” He encouraged design teachers to manage the learning process by telling “the design story.

He thought it essential for youngsters to develop tenacity “so there’s never an idle moment.” All of these elements would manifest themselves in his son’s process of developing the iMac and iPhone for Apple.

Sponsorship/Internship at Roberts Weaver Group

At sixteen, Jony’s talent was already beginning to gain the attention of the design world. Philip J. Gray, the managing director of London’s leading design firm, Roberts Weaver Group, spotted Jony’s work at a teachers’ conference.

His work stood out as being very mature for a sixteen- or seventeen-year-old

Would Gray’s company sponsor Jony though college?

In return for an annual stipend (about £1,500 for each of four years), Jony would promise to work for the design firm after graduation. Sponsoring was very unusual at the time, but Gray agreed.

Top 12% – Diligent Student

In his years at Walton High School, Jony opted to study not only design technology at an advanced level but also chemistry and physics, which was unusual for an arts-oriented student. When he graduated from Walton High School in 1985, he did so with an A in each of his three A-level exams. The hard work of two years of preparation paid off, as earning three top grades wasn’t easy: According to UK government statistics, his results put him in the top 12 percent of students nationwide.

With his academic record and evident talents, Jony had choices. In the end, he did as Phil Gray had advised and opted for Newcastle Polytechnic in the north of England. Product design was to be his main thing.

In his years at Walton High School, Jony opted to study not only design technology at an advanced level but also chemistry and physics, which was unusual for an arts-oriented student. When he graduated from Walton High School in 1985, he did so with an A in each of his three A-level exams. The hard work of two years of preparation paid off, as earning three top grades wasn’t easy: According to UK government statistics, his results put him in the top 12 percent of students nationwide.

Studying at Northumbria University, Newcastle Polytechnic

Students were also required to master hands-on design skills, an emphasis that has continued to this day with the school’s focus on project-based learning. Students at Northumbria traditionally spend a lot of time learning how to make things.

They are taught how to sketch and draw; and how to operate drills, lathes and computer-controlled cutting machines. They are also given time and freedom to experiment with some of the materials and resources in the school and develop a really deep understanding of what they can do with materials.

School Influence

The schooling would distill his work ethic and focus even more. Jony internalized much from his Newcastle experience, including his habit of making and prototyping. His DT education encouraged risks and even rewarded failure, exposing Jony to a very different model from the usual American design school format, which tended to be more prescriptive and industrially focused.

If the education system in America tended to teach students how to be an employee, British design students were more likely to pursue a passion and to build a team around them. If this all sounds familiar, it may be that Jony’s education in Northumbria prepared him very well indeed for his later career at Apple.

First Contact with the Mac

From the first, Jony was astounded at how much easier to use the Mac was than anything else he had tried. The care the machine’s designers took to shape the whole user experience struck him; he felt an immediate connection to the machine and, more important, to the soul of the enterprise. It was the first time he felt the humanity of a product. “It was such a dramatic moment and I remember it so clearly,” he said. “There was a real sense of the people who made it.”

“I started to learn more about Apple, how it had been founded, its values and its structure,” Jony later said. “The more I learned about this cheeky, almost rebellious company, the more it appealed to me, as it unapologetically pointed to an alternative in a complacent and creatively bankrupt industry. Apple stood for something and had a reason for being that wasn’t just about making money.”

Apple stood for something and had a reason for being that wasn’t just about making money.

Concessions to Clients

While Jony’s style seemed to suit RWG, the nature of doing business as a consultancy didn’t. As an outside firm, RWG often had to make concessions to its clients, something that would soon begin to drive Jony crazy.

Third Partner at Tangerine

Jony arrived at Tangerine as a third partner just after Tangerine moved to Hoxton—although he was twenty-three and barely out of design college, Grinyer knew “there was no question of Jony being a junior.” Jony and his wife, Heather, bought a small flat not far away in Blackheath, southeast London.

Voracious Reader

A voracious reader, Jony’s tastes ran to books on design theory, the behaviorist B. F. Skinner and nineteenth-century literature. A museum-goer, too, he and his dad had made many visits over the years to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, one of the world’s leading art and design museums.

Studying the Greats

He studied the work of Eileen Gray, one of the twentieth century’s most influential furniture designers and architects. Modern masters fascinated Jony, among them Michele De Lucchi, a member of Italy’s Memphis group, who tried to make high-tech objects easy to understand by making them gentle, humane and a bit friendly.

He was also fascinated by Dieter Rams, the legendary designer at Braun.

Bob Brunner

Bob Brunner, whom Jony had met on his California trip several years earlier, paid a visit to Tangerine’s studio on Hoxton Street in fall 1991. Having left Lunar Design three years before, Brunner had settled in at Apple, and was now the head of ID. He’d built a killer team of hotshot designers (including several who would later play important roles in developing the iPod, iPhone and iPad).

Apple Consulting gig

Over the course of a few London meetings, Brunner and Tangerine exchanged ideas. Jony created a prototype mouse as a sort of test. The conversations went well and, as a result, Tangerine was given a contract to consult on Juggernaut.

Project Juggernaut was a wide-ranging parallel product investigation. The idea was to explore a suite of mobile products even further off in the future.

Brunner remembered that Jony’s Juggernaut designs stood out because they weren’t based on anything that Apple—or any other computer company—had done before. They were utterly original.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.