We were “po.” That’s a level lower than poor.

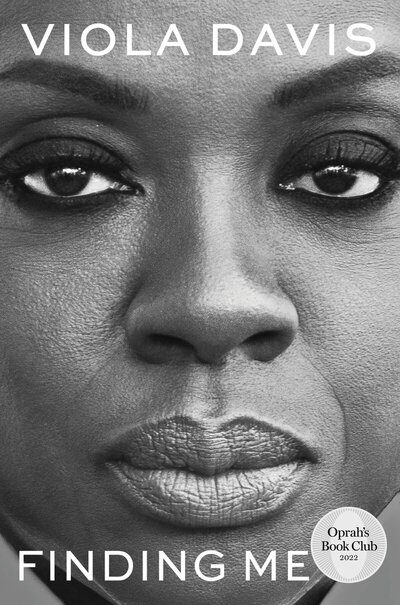

In Finding Me: A Memoir, American actress Viola Davis chronicles her roller-coaster journey from growing up in abject poverty to Hollywood fame. Viola is deeply personal, vulnerable, reflective, funny and emotional about the path she took from being a scared young girl to becoming one of the most influential actresses of her generation. I am a super fan of How to Get Away with Murder, a legal thriller in which Viola stars as Annalise Keating, a law professor; the series is one of the few television shows that I followed religiously when it was airing. I teared up a lot reading Finding Me by Viola Davis as I could connect to her story of growing up in poverty, dealing with childhood trauma, family drama, struggle, determination and eventual triumph.

Success is absolutely wonderful, but it’s not who you are. Who you are is measured by something way more abstract and emotional, ethereal, than outward success.

Finding Me is one of the most inspiring autobiographies have ever read and I would recommend it to anyone that is feeling broken, doubting their greatness, and trying to find their place in the world. Viola shares her struggles of living in abject poverty as a child, her father’s alcoholism and violence towards her mum, bed wetting till 14, sexual abuse and childhood trauma, her healing journey, finding love, hysterectomy, child adoption, and family drama, Hollywood fame, among others.

When you haven’t had enough to eat, when your electricity and heat are cut off, you’re not afraid when someone says life is going to be hard. The fear factor was minimized for me. I already knew fear. My dreams were bigger than the fear.

Viola Davis is an award-winning actress who is the only African-American to achieve the Triple Crown of Acting – a term used in the American entertainment industry to describe actors who have won a competitive Academy Award, Emmy Award, and Tony Award in the acting categories.

I was still that little, terrified, third-grade Black girl. And though I was many years and many miles away from Central.Falls, Rhode Island, I had never stopped running. My feet just stopped moving.

Competitiveness as a tool

“I was being bullied constantly. This was one more piece of trauma I was experiencing—my clothes, my hair, my hunger, too—and my home life being the big daddy of them all. The attitude, anger, and competitiveness were my only weapons. My arsenal. And when I tell you I needed every tool of that arsenal every day, I’m not exaggerating.”

Memories are immortal. They’re deathless and precise. They have the power of giving you joy and perspective in hard times. Or, they can strangle you. Define you in a way that’s based more in other people’s tucked-up perceptions than truth.

Stop Running

At the age of twenty-eight, I woke up to the burning fact that my journey and everything I was doing with my life was about healing that eight-year-old girl. That little third grader Viola who I always felt was left defeated, lying prostrate on the ground. I wanted to go back and scream to the eight-year-old me, “Stop running!”

“I wanted to heal her damage, her isolation. That is, until a therapist a few years ago asked me, “Why are you trying to heal her? I think she was pretty tough. She survived.”

It hit me like a ton of bricks. I was speechless. What? No poor “little chocolate” girl from Central Falls? She’s a survivor?

He leaned forward as if to tell me the biggest secret, or to solve the biggest obstacle of my existence.

“Can you hug her? Can you let her hug YOU?” he asked. “Can you let her be excited about the fifty-three-year-old she is going to become? Can you allow her to squeal with delight at that?”

“ The destination is finding a home for her. A place of peace where the past does not envelop the Viola of NOW, where I have ownership of my story.”

Radical Acceptance

As a child, I felt my call was to become an actress. It wasn’t. It was bigger than that. It was bigger than my successes. Bigger than expectations from the world. It was way bigger than myself, way bigger than anything I could have ever imagined. It was a full embracing of what God made me to be. Even the parts that had cracks and where the molding wasn’t quite right. It was radical acceptance of my existence without apology and with ownership.

As much as I try to chisel into MaMama to get at the core of who she is, I never can. There are decades of suppressed secrets, trauma, lost dreams and hopes. It was easier to live under that veil and put on a mask than to slay them.

Mother

My maternal grandparents, Mozell and Henry Logan, like the other sharecroppers, had a one-room house with a big fireplace. Their daughter, MaMama, the oldest of eighteen children, left school after the eighth grade because she got pregnant, but also because she was beaten a lot in school. I mean beaten to where it broke skin and she bled.

My mother pushed on with her life, nonetheless. She was married and had her first child, my brother, John Henry, at age fifteen. She had my sister Dianne when she was eighteen, Anita at nineteen, Deloris at twenty, and me at twenty-two. Years later, at age thirty-four, she had my sister Danielle.

Father

“Unlike my mother, my father was a simpler man. Dan Davis was born in 1936 in St. Matthews, South Carolina. As far as I know, he had two sisters. For the life of me I can’t remember, but he had, I believe, a poor relationship with his stepfather, whose last name was Duckson.

Abuse elicits so many memories of trauma that embed themselves into behavior that is hard to shake. It could be something that happened forty years ago, but it remains alive, present.

Learned Helplessness

“My older sister Dianne retells a story of my mom and dad having a fight outside. My dad was screaming, “Mae Alice! You want me to stay or leave? Tell me? You want me to stay or go?” My sister was sending telepathic messages in her mind, Please tell him to go! Tell him to go, Mama! But MaMama just screamed, “I want you to stay!” It was a choice that had resounding repercussions.

Parent’s Trauma

I had two parents who were running away from bad memories. Both had undiscovered dreams and hopes. Neither had tools to approach the world to find peace or joy. MaMama worked sporadically in factories and was a gambler.

My father was an alcoholic and would disappear for months at a time when we were really young. He always came back, but by the time I was five I never remember him leaving for any long periods of time. Only later did I realize he was numbing, which is absolutely without question an understandable solution to dealing with a fucked-up world. Then, he would come back, from who knows where, and beat MaMama. Lashing out instead of lashing in.

He loved me. That I know. But his love and his demons were fighting for space within, and sometimes the demons won.

Childhood Imprinting

Imprinting

“I had to stand up to my father, the authority figure. The one who should be taking the glass from ME, teaching ME right from wrong. The most frightening figure in my life and the first man we all ever loved. Frightening?

Without knowing, I had already been imprinted, stamped by their behavior and all that they were. As much as I wanted my life to be better, the only tools I had to navigate the world were given to me by them. How they talked. How they fought. How my mom made concessions. How they loved and who they loved shaped me. If I didn’t bust out of all that, would this exhaustion and depletion be what I would feel after every fight in my life, even the small ones?”

As much as I wanted my life to be better, the only tools I had to navigate the world were given to me by them.

On Poverty – Poor vs Po

“We were “po.” That’s a level lower than poor. I’ve heard some of my friends say, “We were poor, too, but I just didn’t know it until I got older.” We were poor and we knew it. There was absolutely no disputing it. It was reflected in the apartments we lived in, where we shopped for clothes and furniture—the St. Vincent de Paul—the food stamps that were never enough to fully feed us, and the welfare checks. We were “po.” We almost never had a phone. Often, we had no hot water or gas. We had to use a hot plate, which increased the electric bill. The plumbing was shoddy, so the toilets never flushed.

You know, when you’re poor, you live in an alternate reality. It’s not that we have problems different from everyone else, but we don’t have the resources to mask them. We’ve been stripped clean of social protocol. There’s an understanding that everyone is trying to survive and who is going to get in the way of that?

Actually, I don’t ever remember toilets working in our apartments. I became very skilled at filling up a bucket and pouring it into the toilet to flush it. And with our gas constantly being cut off because of nonpayment, we would either go unwashed or would just wipe ourselves down with cold water. And even the wiping down was a chore because we were often without towels, soap, shampoo. . . . I damn sure didn’t know the difference between a washcloth and a bath towel.

“Even on the best days, we never had the right size shoes or clothes. A lot of times, we couldn’t even find socks. We almost never had clothes that were new. Every once in a while, we would go to Zayre’s, a clothing store like J.C. Penney back in the day, and get something on layaway.”

The Paradigm Shift

Viola’s elder sister gave the advice that changed her outlook and sowed the seed for greatness in her. Dianne looked around at the disheveled apartment and said:

“Viola, you don’t want to live like this when you get older, do you?” she asked in a whisper. She didn’t want my mom to hear. “No, Dianne.”

“You need to have a really clear idea of how you’re going to make it out if you don’t want to be poor for the rest of your life. You have to decide what you want to be. Then you have to work really hard,” she whispered.”

“I remember thinking, I just want candy. I couldn’t understand the abstract. I was too young. But something I didn’t have the words for, yet could feel, shifted inside me. “What do I want to be?” The first seed had been planted. Was there a way out?

Achieving, becoming “somebody,” became my idea of being alive. I felt that achievement could detox the bad shit. It would detox the poverty. It would detox the fact that I felt less-than, being the only Black family in Central Falls. I could be reborn a successful person. I wanted to achieve more than what my mother had.

“From age five, because of Dianne, re-creation and reinvention and redefinition became my mission, although I could not have articulated it. She simply was my supernatural ally.”

Abuse Bond

“We were just ensnared in the trap of abuse. The constantly being beaten down so much makes you begin to feel that you’re wrong. Not that you did wrong, but you were wrong. It makes you so angry at your abuser, the one that you’re too afraid to confront, so you confront the easiest target. Those you can. Until your heart gets tired. No one ever, up until that point, talked to us, asked us what our dreams were, asked us how we were feeling. It was on us to figure it out.”

There is an emotional abandonment that comes with poverty and being Black. The weight of generational trauma and having to fight for your basic needs doesn’t leave room for anything else. You just believe you’re the leftovers.

Childhood Trauma

“In my child’s mind, I was the problem. I would retreat to the bathroom, put something against the door so no one would come in, and I’d sit for an inordinate amount of time staring at my fingers and hands and try to erase everything in my mind. I wished I could elevate out of my body. Leave it.”

Dreaming away their problem

“We dreamed away our problems. When Dad was drunk or there was turmoil, my sister Deloris and I would disappear into the bedroom and become “Jaja” and “Jagi,” rich, white Beverly Hills matrons, with big jewels and little Chihuahuas. We would play this game for hours. “Ooh my, Jaja,” Jagi would say, “I bought this fabulous house and my husband bought me this beautiful diamond ring.” We played with such detail that it became transcendent.”

Childhood Sexual Abuse

“We were left with older boys, neighbors who would “babysit” us and unzip their pants while playing horsey with us. My three sisters and I (Danielle wasn’t born yet) were often left unsupervised with my brother in our apartment—sexual curiosity would cross the line. He would chase us. We would lose. And eventually other inappropriate behavior occurred that had a profound effect. I compartmentalized much of this at the time. I stored it in a place in my psyche that felt safely hidden. By hiding it I could actually pretend it didn’t happen. But it did!”

Once again more secrets. Layers upon layers of deep, dark ones. Trauma, shit, piss, and mortar mixed with memories that have been filtered, edited for survival, and entangled with generational secrets. Somewhere buried underneath all that waste lives me, the me fighting to breathe, the me wanting so badly to feel alive.

Deloris, Anita, Dianne, and I were sexually abused. There was penetration with Anita and Dianne. Me and Deloris were touched.

School as a coping mechanism

School was our salvation. We coped by excelling academically. We loved learning. We didn’t want to end up in the same situation as our parents, worrying where the next meal was coming from. School was also our haven. We stayed late, participating in sports, music, drama, and student government. My sisters and I became overachievers, even in areas that didn’t interest us.

Fathers constant violence

“If I got two hours of full sleep, I was lucky. We’d be awakened by a scream, a screech. The only hope, the only blessing, was the fight that didn’t last long. But sometimes their conflicts would last all night or night after night, for days. If it lasted all night, we did not sleep. Imagine your father beating your mom with a two-by-four piece of wood, slamming it on her back, the screams for help, the screams of anger and rage. That trauma would keep me up at night and make me fall asleep in class.”

We were trained in the art of keeping secrets and we never, ever shared with anyone what went on in our home.

Scholarship

Eventually, I received a full ride to college with the Preparatory Enrollment Program scholarship. PEP, as we called it, was the sister program of Upward Bound. I started in a familiar place, Rhode Island College, and space, housing in the same all-girls dormitory—Browne Hall—where I’d spent summers in high school and visited my sister Deloris during the school year. I went into college at seventeen, and like a lot of kids, I wasn’t mature, but I definitely thought I was.

Dianne Inspiration

Even though my mom and dad didn’t go to college—didn’t finish high school—Dianne had driven it into us that We. Were. Going. To. College. She instilled in us that if we did not have a college degree, if we did not find something to do, if we did not focus, if we did not have drive, we were going to be like our parents. I felt if I did not go to college, if I did not get a degree, if I was not excellent, then my parents’ reality would become my own. There was no gray area. Either you achieved or you failed.

Working hard is great when it’s motivated by passion and love and enthusiasm. But working hard when it’s motivated by deprivation is not pleasant.

Exchange Program

My last year, I went on national student exchange to California Polytechnic University in Pomona. I went because I wanted to get out of Rhode Island, out of the cold winters. I just wanted a different scene. The greatest surprise of my life is that in one semester, I flourished. I performed in Mrs. Warren’s Profession, a George Bernard Shaw play. I was a part of an improv group. I took a life-changing public speaking class. I did very well academically and made wonderful friends. It was the first time I got a weave, which was a big deal back in the day. At the time, I felt cute; real cute. I kept that damn weave in until string was hanging down my shoulder.

Manifestation

“Manifestation has always been a part of my life. Either getting on my knees physically or praying silently. And God intervened. In my second year, Juilliard was offering a $2,500 scholarship for any student who wanted to do a summer program that opened them up as artists, helped with their growth, unleashed something within. We had to write a five-page essay explaining it. I wrote that I was lost. That there was no way to unleash passion when you were asked to perform material that not only didn’t touch your heart but wasn’t written for you. I told them of the burden and myopic scope of Eurocentric training. I got the scholarship.”

Pride in Africa

Africa Pride

“Africa made me giddy with joy. Every smell, sound, color affected my senses in a passionate way. No shade of yellow or green or blue was the same. Fabric artists made the dye themselves. They would then make lapas, kufi (hats), grad boo boos (muumuus). Beautiful dark skin was unapologetically darkened by the sun. Every child had many women who would mother them. The ease in which people served each other. The kinky, curly hair, the complexity of the rituals, the numerous different languages.”

Stop making love to something that’s killing you.

The Vicissitudes of Life

There is absolutely no way whatsoever to get through this life without scars. No way!! It’s a friggin’ emotional boxing ring, and either you go one round, four rounds, or forty rounds, depending on your opponent. And by God, if your opponent is you . . . you will go forty. If it’s God, you’ll barely go one because Big Daddy has rope-a-dope down! He’s a shape-shifter. You think you’re fighting him, screaming, punching, begging him for help. And he leaves you with . . . YOU.

Acting : 95% Unemployment Rate

Here’s the truth. If you have a choice between auditioning for a great role over a bad role, you are privileged. That means not only do you have a top agent who can get you in, you are at a level that you would be considered for it. Our profession at any given time has a 95 percent unemployment rate. Only 1 percent of actors make $50,000 a year or more and only 0.04 percent of actors are famous, and we won’t get into defining famous.

The 0.04 percent are the stories you read about in the media. “Being picky,” “dropping agents,” making far less than male counterparts. Never having any regrets in terms of roles they’ve taken. Yada, yada, yada.

Luck is an elusive monster who chooses when to come out of its cave to strike and who will be its recipient. It’s a business of deprivation.

Tough Business

For every one actor who makes it to fame there are fifty thousand more who did exactly the same things, yet didn’t make it. Most of the actors I went with to Juilliard, Rhode Island College, Circle in the Square Theatre, the Arts Recognition Talent Search competition are not in the business anymore. I think I can name six, and many, you wouldn’t even know. It doesn’t speak to their talent, it speaks to the nature of the business. Trust me when I say most were beautiful and talented, and some had incredible agents. It’s an eenie, meenie, miny, mo game of luck, relationships, chance, how long you’ve been out there, and sometimes talent.

You get auditions based on the level you are at. It’s hard to see when your journey to the top had more ease, but in reality, there is no ease. You do what the lucky person did, you have a 99 percent chance of it not ever happening for you.

Family Drama

When you’re making maybe $600 a week and you’re working more than anyone else in the family, they’ll ask for $20, $25. When you’re on Broadway, they’ll ask for $100 and $200. Family starts counting your money because they always feel like you’re making more than you are. Later, it starts getting into the territory of “Buy me a house. Buy me a car.” If you’re not careful, you will go under, because the need is too great, too consistent.

Lack of Boundaries – Inabilities to say NO

“Their burden became my burden. I didn’t know how to say no to requests for food, money, payment for utilities. The needs were so great and began to escalate. I didn’t know that my brother’s problems were not my problems. I had created a life for myself and I would ask God constantly, When do I get to enjoy it fully? Plus, I simply didn’t have the money.”

Studying People

An actor’s work is to be an observer of life. My job is not to study other actors, because that is not studying life. As much as I can, I study people. If you’re my audience, it’s not my job to give you a fantasy. It is my job to give you yourself. In people there is an infinite box of different types, different situations, different behaviors. Those types contradict perceptions. They tear down preconceived notions. They are as complicated and vast as the galaxy itself.

Annalise Keating character changing Viola

Annalise Keating released in me the obstacles blocking me from realizing my worth and power as a woman. Before that, I created a story. Sometimes stories are straight-up lies that you make up because you want what you remember to be different. Sometimes a story is simply how YOU saw that event, how you internalized it. And sometimes the truth simply is. Simply straight-up fact. I was erasing that made-up story. I decided it was time to tell my story, as I remember it, my truth.

All I’ve got is me. And that is enough.

Your depth of understanding of yourself is equal to the depth of understanding a character. We are after all observers of life. We are after all a conduit, a channeler of people. What you haven’t resolved in your life can absolutely become an obstacle in the work that you do.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.