Knowing when to quit is as important as having the will to keep pushing when the going gets tough. When you are constantly pushing and challenging yourself beyond your comfort zone, there will be points where you feel you’ve gone beyond your breaking point. Not all quits are created equally, as some quits are needed for your overall well-being, while some quits are just a strategy for your brain to justify your excuses or bullshit. It is not a matter of if it is going to get tough, but would you be able to recalibrate your mind to push through the pain? To be an athlete, you must have a higher pain tolerance than non-athletic minds. It is tough training for endurance sports such as marathons, triathlons, ultramarathons and ironmans.

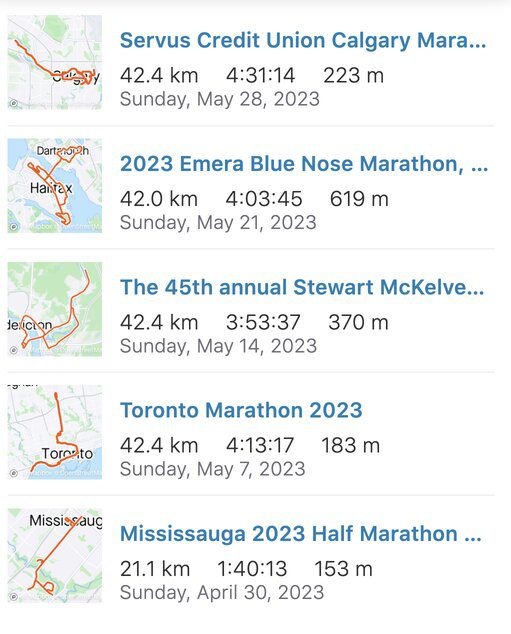

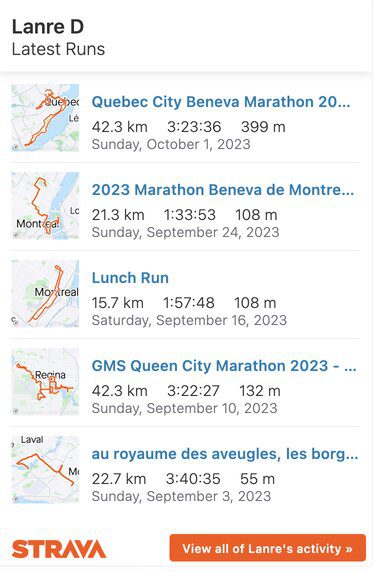

One of the hallmarks of highly successful people and athletes is going the extra mile. To get the results that the most admired people eventually get, one needs to be somewhat obsessed, dedicated and all in. The top 1% in any society are the people who usually give their all, create their luck, consistently show up daily and embrace the struggle. Knowing the difference between addictions, obsessions, compulsions, and dependencies is very important on the path to becoming successful. I have participated in and finished 15 full marathons in the past two years. I trained consistently to achieve my target goals. Knowing the difference is becoming more critical as there is usually a line between the four terms.

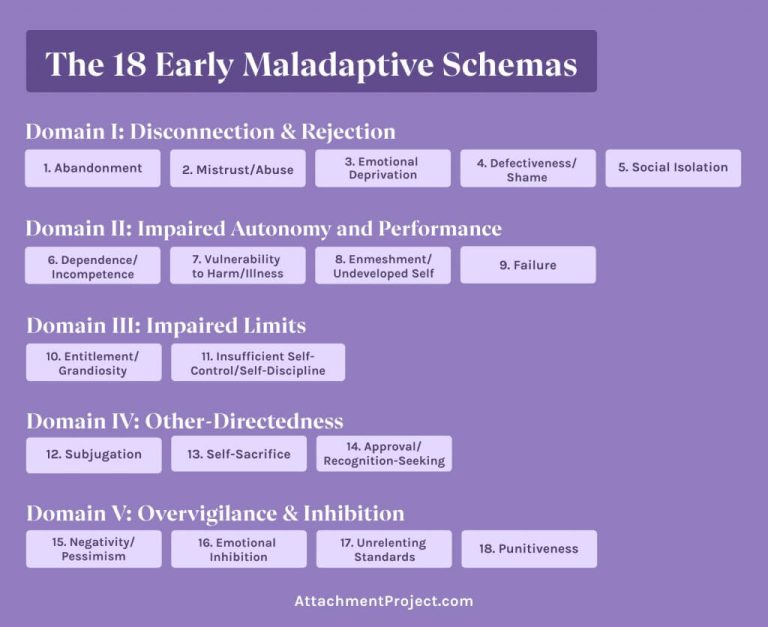

Schema Therapy 1 is an integrative model of psychotherapy developed by American psychologist and founder of the Schema Therapy Institute, Jeffrey E. Young that combines proven cognitive and behavioural techniques with other widely practiced therapies. The main goals of Schema Therapy are to help patients strengthen their Healthy Adult mode, weaken their Maladaptive Coping Modes so that they can get back in touch with their core needs and feelings, heal their early maladaptive schemas to break schema-driven life patterns, and eventually to get their core emotional needs met in everyday life.

The 18 Early Maladaptive Schemas are self-defeating, core themes or patterns that we keep repeating throughout our lives.

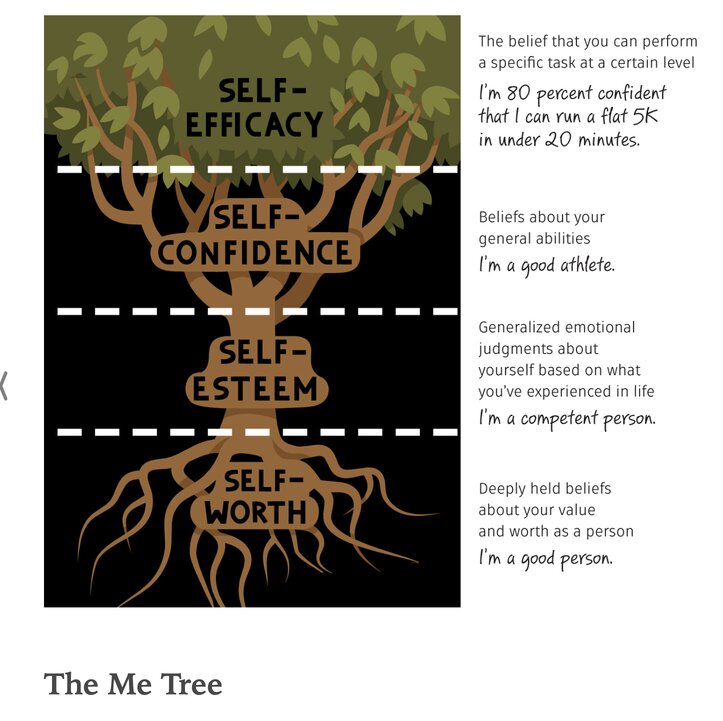

In their book, The Brave Athlete: Calm the F*ck Down and Rise to the Occasion, sports psychologist Dr. Simon Marshall and his wife, World Triathlon Cross Championships Lesley Paterson, describe our self-judgment system using a tree metaphor. The tree comprises a deep root (self-worth), a sturdy trunk (self-esteem), a thick branch (self-confidence) and leaves (self-efficacy).

Our self-judgment systems are hierarchical. The deeper the problem, the more you’re f*cked.

Self-worth – deep roots.

Your self-worth is based on deeply held feelings about your value and worth as a person. It is not about what you do but who you are—your values, morals, passions, and fundamental beliefs about yourself. The extent to which your emotional and psychological needs were met as a kid largely determines your self-worth.

From a young age, we start to express psychological and emotional needs that we are highly motivated to meet: the need for love, security, safety, affirmation, belonging, and so on. If these needs are not met, we try to figure out why. Because our young brains are not capable of analyzing the causes logically and exhaustively, our focus often turns inward. We start to blame ourselves, and the conclusions we settle on are pretty damning: We are not good enough, not worthy enough, not competent enough, and so on. After all, why else would we not get attention, get rejected, or not feel encouraged or protected?

The end result is usually the same: I must be a bad person of little value. The seeds of low self-worth take root. These biased beliefs grow and infect our adult brain like viruses.

A healthy self-worth means that you know your life is valuable and important and that you are loveable. Because self-worth is a relatively stable characteristic of our personality and it affects virtually every self-perception we have, changing it often requires the help of a mental health professional.

Self-esteem – sturdy trunk

Self-esteem is the trunk of the tree because it supports everything above it. Just as a bad root system (low self-worth) can’t create a healthy tree trunk (self-esteem), strong self-esteem is required to support self-confidence (the tree branches). It’s extremely rare to find athletes who are supremely confident but have low self-esteem.

Self-esteem reflects generalized emotional judgments about yourself based on what you believe you’ve experienced, achieved, or accomplished. These “achievements” can be real and tangible (e.g., you’ve done well at school, at work, in sports, etc.) or they can be imagined (e.g., you’ve been told that you’re successful).

Self-confidence – thick branches

Because self-confidence is defined by your perception of your ability, it has a future orientation and predicts what things people will attempt. Self-confidence is the first area in which your self-judgment system can appear differentiated, meaning that you can have strong and weak branches on the same tree. You can have high self-confidence in one area of your life but low self-confidence in another area.

“Even though low confidence can affect other aspects of your life, it rarely affects everything if your underlying self-esteem (tree trunk) is healthy. When you lack self-confidence across the board, the problem is most likely low self-esteem.”

Self-efficacy as leaves

Self-efficacy is a task-specific form of confidence. Technically speaking, self-efficacy refers to your beliefs about your capability of producing a very specific level of performance. Because self-efficacy is situation specific, your confidence to execute a given task may vary depending on the circumstances.

“Self-efficacy is about what you think you can do in very specific tasks, not what you can actually do.”

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Self-schema refers to the thoughts people have about themselves in different areas of life—a sort of mental blueprint of who they are, what they can do, and how they think others perceive them. Think of a self-schema as cognitive scaffolding or a self-stereotype—how your thoughts are assembled about aspects of yourself.

“Athletic self-schema is the cognitive scaffolding of thinking and feeling like an athlete.”

You have self-schema about many different spheres of your life—your identity as a romantic partner, as an employee or student, as a parent, a friend, an athlete, or whatever. All these identities feed into your broader “self-concept,” an overall sense of who you are, what your attributes are, and what and why certain things are important to you.

“The strength of your overall self-concept is determined by the relative importance you give to each of your identities.”

Predictably, your individual self-schemas are interconnected—they talk to one another. After all, thoughts and feelings don’t exist in a vacuum. Feeling crappy or amazing about one aspect of your life can contaminate your other identities. It’s quite unusual to find athletes who suffer from self-schema knots in only one aspect of their lives. This is actually good news because it means that improving the way you think and feel about yourself as an athlete can have a positive knock-on effect in other areas of your life too.

Your athletic self-schema develops from memories of your experiences but is also influenced by expectations of what you think your future self will be like in certain situations. For example, your self-schema as a runner would likely be strong if you ran track and cross-country in college, but you might also have a basic self-schema of being a triathlete even if you’ve never been one. Why? Because you know the discipline and commitment needed to be an athlete and you currently swim and bike to keep fit. In areas where you have little or no experience or you’re simply indifferent, you might have no schema at all.

Your self-schema shapes your expectations of what you think you can do, what you attempt and persist at, how you explain your success and failure, and how you want others to see you in certain areas of life.

Understanding an athlete’s self-schema is important because it helps us make predictions about the sorts of situations that are likely to feel stressful, challenging, and rewarding to you and, critically, what things we need to focus on to help you improve confidence and grit, take responsibility, and learn acceptance skills (“owning it”). This means that building a mature athletic identity requires that your athletic self-schema is relatively free of bugs and gremlins.

Your athletic identity is not about your speed, placings, leanness, or amount of training. A mature athletic identity is simply a special configuration of thoughts about emotions.

Athletic Identity

Athletic identity is all about thinking and feeling like an athlete. Athletic identity has nothing to do with how fast you are, how much racing you do, or how much you train. Although these details can all be signs of having a mature athletic identity, they’re certainly not required. We develop our inner and outer athletic identities when we do endurance sports—we learn skills and techniques, we develop fitness, and we interact with fellow athletes. A sign that our internal athletic identity is maturing is our use of the sport to define our athleticism. I’m a triathlete. I’m a CrossFit® athlete. I’m a runner. A sign that our outer athletic identity is getting stronger comes when we notice others are calling us that too.

“Changing your self-schema is an inside-to-out strategy (targeting thoughts to change feelings to change actions)”

Personal Experience: My Marathon Journey

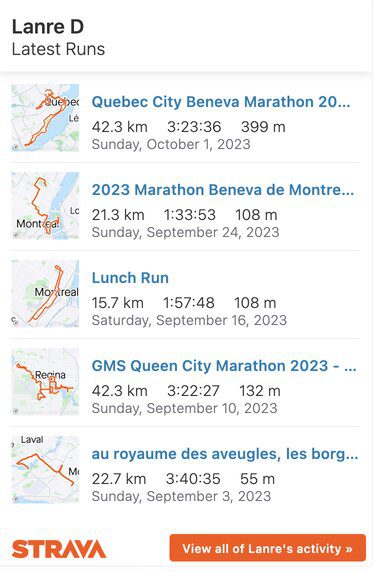

I started my marathon running adventure in 2013 after losing my closest cousin, and I was looking for an outlet for the pain, grief and disillusionment I was experiencing in that period of my life. I stumbled upon a marathon race in two months and participated in much training. My time for my first marathon was 5 hours plus, and it was tough, even brutal, at the time. I ran, walked, limped, but I ultimately finished. In the past ten years, I have since run 25+ full marathons, with fifteen full marathons finished in the past two years. I ran six full marathons in 2022 and nine full marathons in 2023. My journey to developing my Athletic Identity and Self-schema has not been smooth. It has been filled with ups and downs, self-doubt, failures, dejection, triumphs, insights, personal records and self-confidence.

One of the identities that I have developed in the past ten years that I am most proud of is being a reader (life-long learner) and a runner. I run multiple marathons yearly, not because I have to but because I love the lessons I learn and the person I am becoming as a result of participating in these marathons. I have learned more from my ten years of experience running marathons than my over 3 decades of formal schooling. Marathon running has helped me become more precise in my self-schema, and developing an identity as an athlete and go-getter makes it worthwhile.

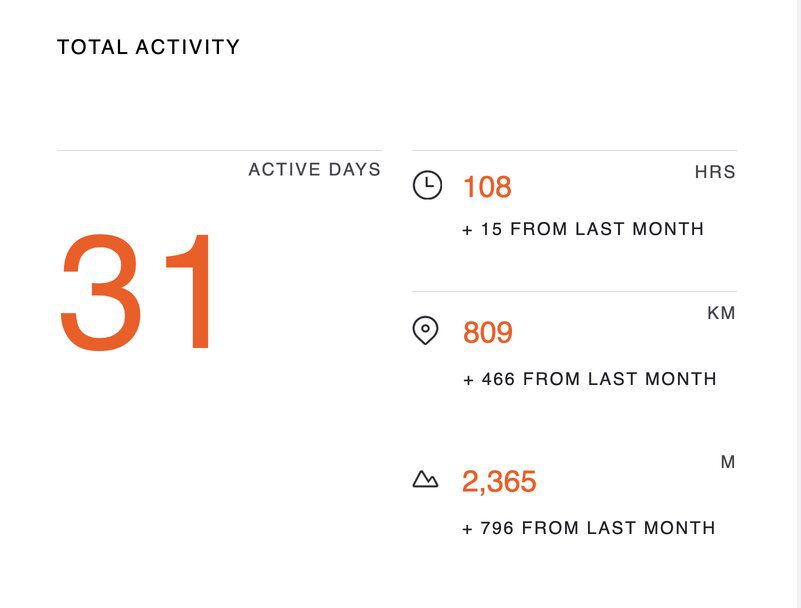

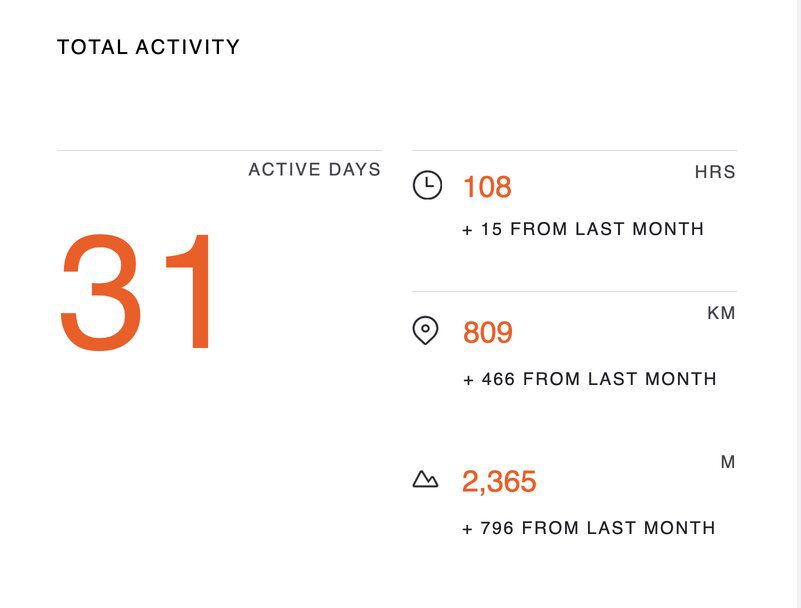

I reduced my full marathon personal best time from 3 hours 44 minutes to 3 hours 20 minutes last year at the 2023 GMS Queen City Marathon in Regina, Saskatchewan. It was a great moment, as I had been training hard before breaking my record. I had logged 108 hours of cross-training time in the gym and also ran almost every day in July covering a distance of 809 KM. By breaking this record, I had a renewed resolve that I could achieve anything that I set my mind to do.

One of the great lessons learned from running multiple marathons is the value of hardwood and preparation. As the saying goes, you can outplay your training. We play the way we train. The marathon is a great metaphor for life as your input ultimately determines your output. If you training at a sub-3 hours marathon time in training, executing during race day is not going to be hard. By running these multiple marathons, I have a clear self-schema that makes me believe I could run a time that I have trained for and can execute,

Since breaking the sub-3:30 marathon time, I have run three full marathons with great times:

- Beneva Quebec City Marathon | Quebec | October 1st, 2023 | 3;20:59

- Royal Victoria Marathon | British Columbia | October 8th, 2023 | 3:31:15

- Prince Edward Island Marathon | Charlottetown | October 15, 2023 | 3:25:13

My self-schema is changing because I am putting in the work. I intend to run a sub-3-hour marathon time in 2024. I know it will be tough, but I know what to do. Put in the same amount of time, energy, commitment, and dedication as I did in reducing my personal best by 24 minutes in 2023. Remember where I started in 2013, not athletic to clocking 854 hours of training time in 2023. It took over a decade to define my self-schema and develop my athletic identity.

The story’s moral: You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great. To achieve any goal whether it is running a marathon, writing a book, learning a foreign language, becoming financially independent or learning a programming language, one has to keep pushing and never doubt yourself. To achieve my sub-3 hour marathon goal, I will have to recalibrate my self-schema as someone who can run a sub-3 hour marathon.

You don’t have to be great to start, but you have to start to be great.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

The 20 Mile March is a concept popularized by author Jim Collins in his book, Great by Choice: Uncertainty, Chaos, and Luck–Why Some Thrive Despite Them All. Collins remarked that enterprises that prevail in turbulence self-impose a rigorous performance mark to hit consistently—like hiking across the United States by marching at least 20 miles daily. The march imposes order amidst disorder, discipline amidst chaos, and consistency amidst uncertainty. The 20-mile march works only if you hit your march year after year; if you set a 20-mile march and then fail to achieve it, you may well get crushed by events.

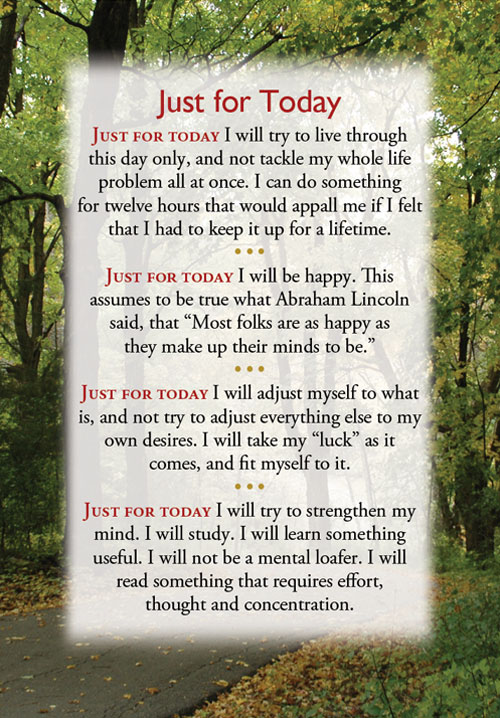

“Just for Today” is one of the strategies used by many twelve-step programs. Twelve-step programs are mutual aid programs which support recovery from substance, and behavioral addictions. The Twelve-step method is a roadmap for those seeking recovery from addictions such as alcoholism, drugs, sex, pornography, eating disorders, codependency, relationship problems, smoking, debt, work, gambling, spending, and technology addiction etc. “Just for Today” is a set of daily meditations, and reflections for people dealing with various addiction and it meant for them to focus on their recovery one day at a time.

A Taoist story tells of an old man walking along a riverbank. The river was swift, and powerful rapids led to a tall waterfall just downstream. Suddenly, the man stumbled and fell into the river and was swept up by the powerful currents.

Onlookers watched with horror, worried for the man’s life as he was carried downstream and over the edge of the waterfall. They rushed to the edge of the cliffs and peered down. To their astonishment, the old man stood on the rocky banks at the bottom of the falls. He was soaked from head to toe but unharmed and had an unassuming smile.

The term Fucked-up, Insecure, Neurotic, and Emotional was popularised by the rock band Aerosmith, it was the second track on the band’s 1989 album Pump. It is also used in rehabilitation programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous as a phrase to describe the feeling of life being out of control and constant chaos. In the movie, “The Italian Job,” FINE is described as “freaked out, insecure, neurotic, and emotional.”

Other references to the FINE acronym in popular culture include A scene from the British crime drama television series Happy Valley (series 1 episode 4), also referenced in the American slasher film Scream 2 and the 2018 American superhero movie Deadpool 2; the following scene unfolds:

In his bestselling book, Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones, author James Clear writes about a powerful tool called the implementation-intention tool, which is a great tool for achieving and starting new habits. He writes:

IN 2001, RESEARCHERS in Great Britain began working with 248 people to build better exercise habits over the course of two weeks. The subjects were divided into three groups.

- The first group was the control group. They were simply asked to track how often they exercised.

- The second group was the “motivation” group. They were asked not only to track their workouts but also to read some material on the benefits of exercise. The researchers also explained to the group how exercise could reduce the risk of coronary heart disease and improve heart health.

- The third group received the same presentation as the second group, which ensured that they had equal levels of motivation. However, they were also asked to formulate a plan for when and where they would exercise over the following week. Specifically, each member of the third group completed the following sentence:

“During the next week, I will partake in at least 20 minutes of vigorous exercise on [DAY] at [TIME] in [PLACE].”

In the first and second groups, 35 to 38 percent of people exercised at least once per week. (Interestingly, the motivational presentation given to the second group seemed to have no meaningful impact on behavior.) But 91 percent of the third group exercised at least once per week—more than double the normal rate.

The Implementation Intention is a plan you make beforehand about when and where to act.

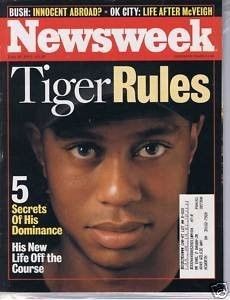

In 2001, writer and former editor at Newsweek Devin Gordon wrote a profile about American professional golfer Tiger Wood which is still as relevant as ever. I first became aware of the Newsweek article by listening to Ed Mylett Podcast. Ed considers the article to be one of the most impactful articles that he has ever read and he has carried the physical magazine with him for 25 years. I agree with Ed, the article is really good as it contains five strategies for dominating in life and career.

Three years younger than Michael Jordan when he won his first NBA title, Woods is emerging as the best of an elite crop of athletes: the dominators. Obviously, stars like Tiger are supremely gifted physically, but it goes well beyond that: dominators possess uncommon emotional control and unlimited reservoirs of passion. What makes these athletes so much better than even the finest in their sport? NEWSWEEK asked a dozen true dominators–Wayne Gretzky, Martina Navratilova, Joe Montana, Jordan (a close friend of Woods’s; following story), and more–what it takes to be the best of the best.

Two TRAVELING MONKS reached a town where there was a young woman waiting to step out of her sedan chair. The rains had made deep puddles and she couldn’t step across without spoiling her silken robes. She stood there, looking very cross and impatient. She was scolding her attendants. They had nowhere to place the packages they held for her, so they couldn’t help her across the puddle.

The younger monk noticed the woman, said nothing, and walked by. The older monk quickly picked her up and put her on his back, transported her across the water, and put her down on the other side. She didn’t thank the older monk, she just shoved him out of the way and departed.

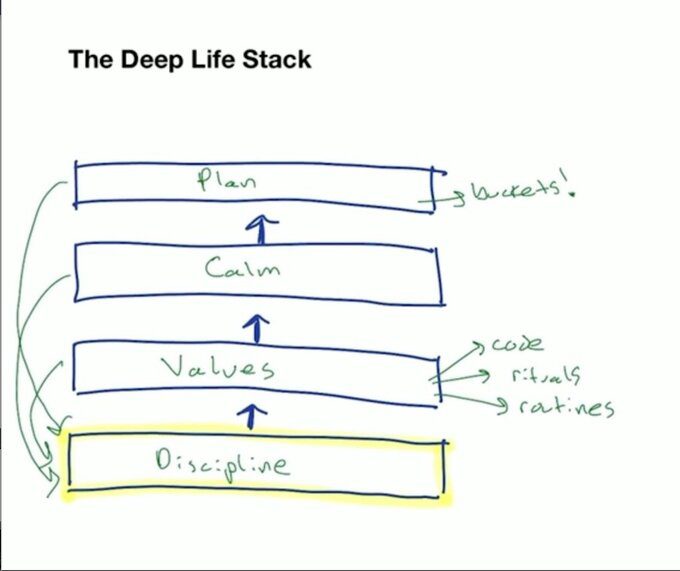

Cal Newport is the author of two of the most influential books I have ever read in my quest to become more productive: Deep Work and Digital Minimalism. Both books really shaped my view on using social media, leading a productive life, and eliminating non-essentials. I am also an ardent listener of his podcast – Deep Questions with Cal Newport. In episode 252: The Deep Life Stack, cal elaborates on what he calls “The Deep Life Stack,” an approach to cultivating a deep life that starts with overhauling the person before making the big decisions. I found the idea to be very compelling and a great tool to lead a more productive life.

Cal is an MIT-trained computer science professor at Georgetown University who also writes about the intersections of technology, work, and the quest to find depth in an increasingly distracted world.

Mellody Hobson is the Co-CEO, President, and Chairman of the Board of Trustees, at Ariel Investment Trust, a Chicago-based investment firm that specializes in small and mid-capitalized stocks based in the United States. Mellody currently serves as Non-Executive Chair of the Board of Starbucks Corporation and an independent director of JPMorgan Chase. In her Masterclass on Strategic Decision-Making, she shared tips and strategies for becoming a strategic thinker and also delves into two real-life case studies that exemplify how she applied these tools in complex business situations.

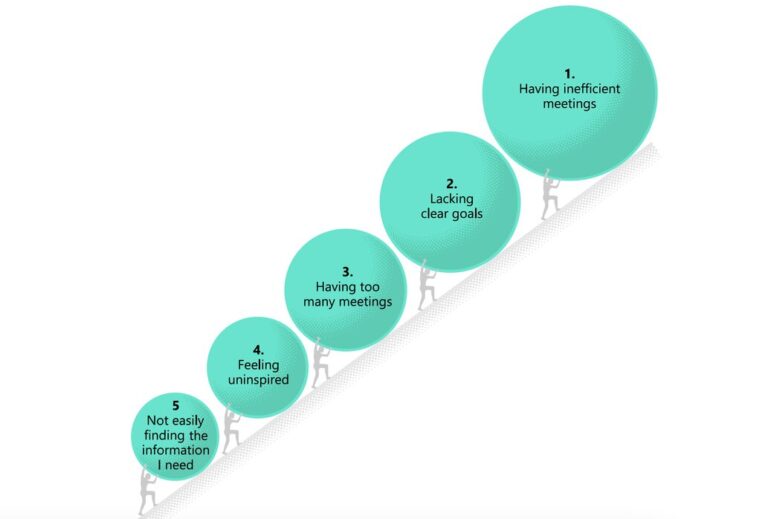

Across the Microsoft 365 apps, the average employee spends 57% of their time communicating (in meetings, email, and chat) and 43% creating (in documents, spreadsheets, and presentations).

A recently pubished report by Microsoft: The 2023 Work Trend Index: Annual Report, revealed that workers are spending at least full working days (57% of their time communicating in meetings, email, and chat). The report noted an urgent need to make meetings more effective as people report inefficient meetings as their number one productivity disruptor. The top 5 obstacles to work productivity, according to the Microsoft Work Trend Index Report, are: Having inefficient meetings, Lacking clear goals, Having too many meetings, Feeling uninspired, and Not easily finding the information I need.

Workers spend at least full working days (57% of their time communicating in meetings, email, and chat).