Swimming is, by our human definition, a constant state of not drowning.

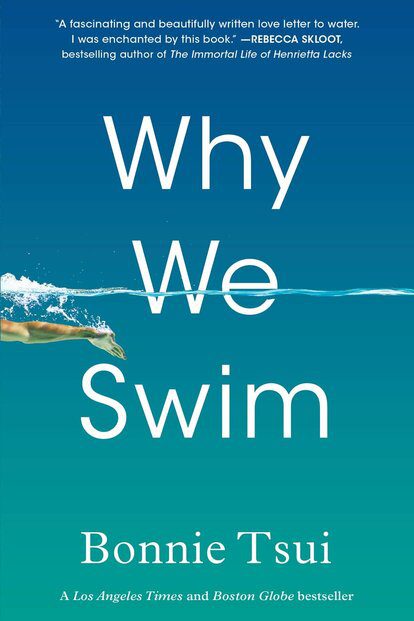

In Why We Swim, New York Times contributor and swimmer Bonnie Tsui writes about the art of swimming, profiled swimming enthusiasts and long-distance swimmers such as Lewis Pugh, Lynne Cox, Kim Chambers, Diana Nyad, Gertrude Ederle, Olympic champions such as Michael Phelps, Katie Ledecky, Dara Torres.

She also writes about everyday people such as a Baghdad swim club that meets in Saddam Hussein’s former palace pool, modern-day Japanese samurai swimmers, and an Icelandic fisherman who improbably survives a wintry six-hour swim after a shipwreck. Bonnie investigates what it is about water that seduces us, and why we come back to it again and again.

On Swimming

Of course, it has to do with survival: Somewhere along the way, swimming helped us to get from one prehistoric lakeshore to another and escape predators of our own; to dive for that trove of bigger shellfish and get to new sources of food; to venture across oceans and settle new lands; to navigate all manner of aquatic perils and see swimming as a source of joy, pleasure, achievement. To arrive at this day, to talk about why we swim.

To find rhythm in the water is to discover a new way of being in the world, through flow. This is about our human relationship to water and how immersion can open our imaginations.

The book is an investigation of what seduces us to water, despite its dangers, and why we come back to it again and again. The act of swimming can be one of healing, and health—a way to well-being. Swimming together can be a way to find community, through a team, a club, or a shared, beloved body of water. We have only to watch each other in the water to know that it creates the space for play. If we get good enough at the thing, it can be an engine of competition—a way to test our mettle, in the pool or open water. Swimming is about the mind, too. To find rhythm in the water is to discover a new way of being in the world, through flow. This is about our human relationship to water and how immersion can open our imaginations.

More than 70 percent of the planet is covered by water; 40 percent of the global population lives less than sixty miles from the coast.

The practice of swimming, and the different ways in which we teach ourselves to swim, is part of that collective cultural knowledge. When it comes to swimming, it is not just the how-to—the formal instruction—that is critical but also the ways we communicate the importance of that knowledge, through the stories we tell.

Swimming is a way for us to remember how to play.

Water Therapy

The pressure of water itself on your body plays a part in swimming for health. When you immerse yourself in water, it pushes blood away from the extremities and toward your heart and lungs; this temporarily elevates your blood pressure and makes your heart and lungs work harder. The process builds efficiency and endurance in the cardiovascular system, leading to lower blood pressure over time. And when you swim, the water provides gentle, all-around resistance for your muscles to work against.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt suffered from polio; while in office, he had a swimming pool installed in the White House and swam for therapy several times a day. President John F. Kennedy, who endured near-constant back pain and a life of excruciating health miseries, loved the pool so much he swam before lunch and dinner. FDR’s pool remains there today, beneath what is the press pool briefing room.

Swimming is particular in its activation of deep breathing. It’s the nature of the exercise: you take a big breath, hold it, and then release it slowly.

On Drowning

Swimming is, by our human definition, a constant state of not drowning. The Oxford English Dictionary emphasizes the propulsion of the body through water with one’s limbs and a position afloat on the water’s surface. To drown is to die through immersion or submersion—the body under the surface—in water and inhalation of that water. We know from the most ancient of times that the boundary between the two states of being is thin; it grows permeable when we’re not looking.

Swimming is, by our human definition, a constant state of not drowning.

Some of the benefits of swimming derive, ironically, from daring to come as close as we can to this very fight for survival. That’s the sublime: the awe and the terror, together. Those moments of panic, the electric flashes of fear, are elucidating, exhilarating. The act of getting in is a small defiance of death itself.

Every year, 372,000 people die from drowning. That’s more than forty people every hour, every day. In 2014, the World Health Organization released a global report on drowning to launch the first worldwide strategic prevention effort. Their goal: to target drowning as a public health challenge.

Every year, 372,000 people die from drowning. That’s more than forty people every hour, every day.

Just because you know how to swim, of course, doesn’t mean you won’t drown. There are all kinds of factors that contribute to drowning incidents; for example, there is some research that shows parents are less attentive to their young children in water when those children have had swim instruction. But the vast majority of drownings happen in low- and middle-income countries where people have close, daily contact with water—among fishermen, say, or farmers ferrying their goods by river or children fetching water from a well or pond.

Trusting the Process

It can take a long time to see if someone is going to be a good swimmer, to the tune of years, really. Press rewind on every Olympic swimmer—Katie Ledecky, too—and each starts out as one of those squishy little swimmers.

Many of us have joined a swim team at one time or another, and there is a shared foundational experience here that’s worth examining. Battle past the desperate life-or-death phase of swimming, and you begin to appreciate how good the water feels. Join a team, and you begin to appreciate the company you keep. Competition happens when you get good enough at swimming to want to be better.

Right from the start, it becomes about speed and technique. You work to refine your strokes, over and over again, to achieve—what? The win, yes, but that’s fleeting, especially at this stage. Parse out the win for even the youngest swimmers and you realize that it’s the rare coming together of effort and timing that lifts you for days. That’s a feeling that any swim team swimmer knows, no matter their level.

FLOW

Water is H2O, hydrogen two parts, oxygen one, but there is also a third thing, that makes it water and nobody knows what it is.—D. H. LAWRENCE, “The Third Thing”

Flow is what the groundbreaking Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi explains as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter.” The experience of said activity—swimming, say, or playing music—is so entirely enjoyable, he says, “that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it.” I think of frigid waters, crack-of-dawn workouts, shoulder injuries, all the money I’ve spent on bikinis.

Nearly three decades ago, Csikszentmihalyi was the first to use the word flow to describe the experience of being so totally immersed that the self seems to fall away, along with any awareness of the passage of time

Media

- Fishpeople | Lives Transformed by the Sea

In the documentary Fishpeople, filmmaker Keith Malloy interviews surfers, spearfishers, swimmers, and others to create a vivid picture of how their lives are transformed by the sea. These are people who live in the water for all of its sensory immediacy and also for the outlook it fosters. At some point or another, they all feel compelled to speak about how the ocean brings them to a hyperawareness of our precarious existence.

- Lidia Yuknavitc’s “I Will Always Inhabit the Water,” essay

“The great intake of air, a breath that keeps a human able to move through water as if we were not gone from our breathable blue past.”

- 1937 Rachel Carson’s “Undersea,” essay:

“Individual elements are lost to view, only to repair again and again in different incarnations in a kind of material immortality,”

I recently started swimming and I have been obsessed with figuring out how to get better in the pool/water. It was my newfound passion that led me to read Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim and I was engrossed with her narration of the beauty of swimming. Bonnie does a great job of writing glowingly about swimming, the history of swimming, the early pioneers, fear of water, passion, cultures, and getting in flow with water. A very good read and I would recommend it for anyone that is trying to learn to swim or loves swimming. I am not yet great at swimming but my dedication to the sport would make me great at it soon.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.