Too Soon Old, Too Late Smart: Thirty True Things You Need to Know Now is a collection of thirty common sense wisdom by the celebrated psychologist and military veteran Dr. Gordon Livingston. He reflects on the lessons learned from his patients, time in the US Army, and most importantly on the roller coaster of life.

Favourite Takeaways -Too Soon Old, Too Late Smart

1: If the map doesn’t agree with the ground, the map is wrong

Over the many years, I have spent listening to people’s stories, especially all the ways in which things can go awry, I have learned that our passage through life consists of an effort to get the maps in our heads to conform to the ground on which we walk. Ideally, this process takes place as we grow.

Our parents teach us, primarily by example, what they have learned. Unfortunately, we are seldom wholly receptive to these lessons. And often, our parents’ lives suggest to us that they have little useful to convey, so that much of what we know comes to us through the frequently painful process of trial and error.

The Map

This is the map we wish to construct in our heads: a reliable guide that allows us to avoid those who are not worthy of our time and trust and to embrace those who are. The best indications that our always-tentative maps are faulty include feelings of sadness, anger, betrayal, surprise, and disorientation. It is when these feelings surface that we need to think about our mental instrument of navigation and how to correct it, so that we do not fall into the repetitive patterns of those who waste the learning that is the only consolation for our painful experience.

2: We are what we do

“The three components of happiness are something to do, someone to love, and something to look forward to. If we have useful work, sustaining relationships, and the promise of pleasure, it is hard to be unhappy. ”

We are always talking about what we want, what we intend. These are dreams and wishes and are of little value in changing our mood. We are not what we think, or what we say, or how we feel. We are what we do.

Conversely, in judging other people we need to pay attention not to what they promise but to how they behave. This simple rule could prevent much of the pain and misunderstanding that infect human relationships. “When all is said and done, more is said than done.

“Most of the heartbreak that life contains is a result of ignoring the reality that past behavior is the most reliable predictor of future behavior.“

3: It is difficult to remove by logic an idea not placed there by logic in the first place.

The things we do, the prejudices that we hold, and the repetitive conflicts that afflict our lives are seldom the products of rational thought.

Autopilot

The motivations and habit patterns that underlie most of our behavior are seldom logical; we are much more often driven by impulses, preconceptions, and emotions of which we are only dimly aware.

If most of our behavior is driven by our feelings, however unclear they may be, it follows that to change ourselves we must be able to identify our emotional needs and find ways of satisfying them that do not offend those upon whom our happiness depends. If we wish, as most of us do, to be treated with kindness and forbearance, we need to cultivate those qualities in ourselves.

4: The statute of limitations has expired on most of our childhood traumas.

The stories of our lives, far from being fixed narratives, are under constant revision. The slender threads of causality are rewoven and reinterpreted as we attempt to explain to ourselves and others how we became the people we are.

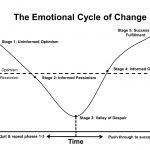

Change is the essence of life. It is the goal of all psychotherapeutic conversation. In order for the process to proceed, however, it must move beyond simple complaint. Complaining about how one feels, or about repetitive behaviors that produce familiar and unhappy results, is just the beginning of a process.

5: Any relationship is under the control of the person who cares the least.

Each person’s assessment of a prospective mate using these standards creates a certain set of expectations. It is the failure of these expectations over time that causes relationships to dissolve.

6: Feelings follow behavior.

Most people know what is good for them, know what will make them feel better: exercise, hobbies, time with those they care about. They do not avoid these things because of ignorance of their value, but because they are no longer “motivated” to do them. They are waiting until they feel better. Frequently, it’s a long wait.

7: Be bold, and mighty forces will come to your aid.

We carried the burdens of time and fate and our hearts were weighted with the knowledge of those who could not return and whose stories were lost to all except those who loved them.

8: The perfect is the enemy of the good.

Most of us devote great amounts of time and energy to efforts to assert control over what happens to us in our uncertain progress through life. We are taught to pursue an elusive form of security, primarily through the acquisition of material goods and the means to obtain them. There is a kind of track that we are put on early in life with the implicit suggestion that, if we “succeed,” we will be happy and secure.

9: Life’s two most important questions are “Why?” and “Why not?” The trick is knowing which one to ask.

Acquiring some understanding of why we do things is often a prerequisite to change. This is especially true when talking about repetitive patterns of behavior that do not serve us well. This is what Socrates meant when he said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” That more of us do not take his advice is testimony to the hard work and potential embarrassment that self-examination implies.

Life is a gamble in which we don’t get to deal the cards, but are nevertheless obligated to play them to the best of our ability.

10: Our greatest strengths are our greatest weaknesses.

A certain amount of compartmentalization is necessary to succeed in the different areas of our lives. Juggling our multiple responsibilities—worker, partner, parent, friend—is a challenge. We think of ourselves as the same person whatever we may be doing at the moment. But our different roles demand different attitudes. If we try to impose a businesslike, vertically integrated decision-making structure on our families, we are likely to encounter resentment and resistance. Conversely, if our style tends to be impulsive, superficial, and pleasure-seeking, we may find it difficult to succeed at work.

11: The most secure prisons are those we construct for ourselves.

When we think about loss of freedom, we seldom focus on the ways in which we voluntarily impose constraints upon our lives. Everything we are afraid to try, all our unfulfilled dreams, constitute a limitation on what we are and could become. Usually it is fear and its close cousin, anxiety, that keep us from doing those things that would make us happy. So much of our lives consists of broken promises to ourselves.

12: The problems of the elderly are frequently serious but seldom interesting.

Old age is commonly seen as a time of entitlement. After long years of working, the retiree is presumably entitled to leisure, social security, and senior discounts. Yet all of these prerogatives are poor compensation for the devalued status of the elderly. The old are stigmatized as infirm in mind and body. Apart from their continuing role as consumers, the idea that old people have anything useful to contribute to society is seldom entertained.

13: Happiness is the ultimate risk.

Our feelings depend mainly on our interpretation of what is happening to us and around us—our attitudes. It is not so much what occurs, but how we define events and respond that determines how we feel. The thing that characterizes those who struggle emotionally is that they have lost, or believe they have lost, their ability to choose those behaviors that will make them happy.

14: True love is the apple of Eden

Childhood is a series of disillusionments in which we progress from innocent belief to a harsher reality. One by one we leave behind our conceptions of Santa Claus, the tooth fairy, the perfection of our parents, and our own immortality. As we relinquish the comfort and certainty of these childish ideas, they are replaced with a sense that, thanks to Adam and Eve, life is a struggle, full of pain and loss, ending badly.

15: Only bad things happen quickly.

When we think about the things that alter our lives in a moment, nearly all of them are bad: phone calls in the night, accidents, loss of jobs or loved ones, conversations with doctors bearing awful news. In fact, apart from a last-second touchdown, unexpected inheritance, winning the lottery, or a visitation from God, it is hard to imagine sudden good news. Virtually all the happiness-producing processes in our lives take time, usually a long time: learning new things, changing old behaviors, building satisfying relationships, raising children. This is why patience and determination are among life’s primary virtues.

16: Not all who wander are lost.

Of all the things that define us, education appears to be the most highly correlated with success. It is little wonder, then, that we are urged throughout childhood to do well in school and take our successive graduations as necessary steps toward a comfortable life. There is a promise implicit in this process: follow instructions, please others, obey the rules, and happiness will be yours.

There are no maps to guide our most important searches; we must rely on hope, chance, intuition, and a willingness to be surprised.

17: Unrequited love is painful but not romantic.

We seek the unconditional approval of the good parent, the ultimate in emotional security. If we got this as a child we want it again; if, like most of us, we did not, still we wish for it as a shield in an uncertain, often uncaring, world. Our desire to be accepted just as we are is so strong that we sometimes project our need for love onto another and ignore the fact that it is not being returned.

In their saddest form these feelings are directed at people we don’t even know. Movie stars are frequent objects of adoration based on how they appear or the characters they play. Their privacy is routinely invaded by fanatical admirers convinced that they might somehow induce reciprocal feelings if only they were given the chance. Sometimes these frustrated emotions are transmuted into something different.

18: There is nothing more pointless, or common, than doing the same things and expecting different results.

The process of learning consists not so much in accumulating answers as in figuring out how to formulate the right questions. This is why psychotherapy takes the Q&A form that it does. This is not, as many think, a trick on the therapist’s part to lead the client in a known direction. It represents a joint exploration, an inquiry into motives and patterns of thought and behavior, trying always to make connections between past influences and present conceptions of what it is we want and how best to get it.

19: We flee from the truth in vain

20: It’s a poor idea to lie to oneself.

Authenticity is a prized ideal. Though required to play a variety of roles in our daily lives, we would like to see ourselves as having a relatively stable identity that expresses our core values over time. Most of us also place a lot of importance on the way we are seen by those whose opinions we respect.

There are few human attributes that excite more contempt than hypocrisy. People whose actions do not accord with their professed beliefs become objects of derision. Most of the scandals that entertain us are based on a disconnect between words and behavior: adulterous preachers, deceitful politicians, drug-abusing moralists, pedophile priests. Our outrage is balanced by our fascination, fueled by the guilty knowledge of our own failure to conform our behavior to the standards we publicly endorse.

21: We are all prone to the myth of the perfect stranger.

No element of dissatisfaction with our lives is more common than a belief that we have in our youth made the wrong choice of partner. The fantasies generated thereby often take the form of a conviction that there exists somewhere the person who will save us with his or her love. Much of the infidelity that is the hallmark of unhappy marriages rests on this illusion.

Some estimates of marital infidelity by age forty place it at fifty to sixty-five percent of married men and thirty-five to forty-five percent of married women. In a society whose dominant expressed marital value is monogamy, these are numbers that indicate not just a high level of hypocrisy, but some serious dissatisfaction with our partners. What is it that people are looking for outside their marriages?

22: Love is never lost, not even in death.

This is what passes for hope: those we have lost evoked in us feelings of love that we didn’t know we were capable of. These permanent changes are their legacies, their gifts to us. It is our task to transfer that love to those who still need us. In this way we remain faithful to their memories.

23: Nobody likes to be told what to do.

We are not obedient people. Most of us are the descendants of those who undertook dangerous voyages in pursuit of freedom and self-determination and were willing to sacrifice a great deal in defense of these ideas. We are genetically programmed to question authority.

Still, we try to tell each other what to do. Our desire for control and a belief that we know how things should overcome our common sense about how people react to orders. This is especially true of parents. Even in our child-centered (some might say child-obsessed) society, we think we know best how to “guide” our children so that they will fulfill their above-average potential as students, athletes, and American success stories.

Awfulizing: The idea that any relaxation in standards or vigilance is the first step toward failure, degradation, and the collapse of civilization as we know it.

24: The major advantage of illness is that it provides relief from responsibility.

When no other relief is available to us, some form of illness or disability is one of the few socially acceptable ways of relinquishing the weight of responsibility, if only for a little while. Instead of being expected to get up each morning and face tasks that we abhor, we are, when sick, told to “take it easy.” For some people, trapped on a treadmill of obligation, the disadvantages of diminished functioning and physical pain are counterbalanced by the relief of lowered expectations.

25: We are afraid of the wrong things.

We live in a fear-promoting society. It is the business of advertisers to stoke our anxieties about what we have, what we look like, and whether we are sexually adequate. A dissatisfied consumer is more apt to buy. Likewise, the purveyors of television news attempt to hold our interest by scaring us with stories of violent crime, natural disasters, threatening weather, and environmental hazards.

Even in good times the public perception of the risk of becoming a crime victim is exaggerated. We arm ourselves against mythical intruders and ignore the reality that family members are the most likely victims of the guns we buy. Meanwhile, the real risks to our welfare—smoking, overeating, not fastening seat belts, social injustice, and the people we elect to office—provoke little anxiety.

26: Parents have a limited ability to shape children’s behavior, except for the worse.

To imagine that we are solely, or even primarily, responsible for the successes and failures of our children is a narcissistic myth. It is obvious that parents who abuse their children—physically, psychologically, or sexually—can inflict serious and lasting damage upon them. It does not follow, however, that parents who fulfill their primary obligation to love their children and provide a stable and nurturing environment for them to grow are responsible for the outcome of their kids’ efforts.

27: The only real paradises are those we have lost.

What happens as we try to come to terms with our pasts is that we see our lives as a process of continual disenchantment. We long for the security provided by the comforting illusions of our youth. We remember the breathless infatuation of first love; we regret the complications imposed by our mistakes, the compromises of our integrity, the roads not taken. The cumulative burdens of our imperfect lives are harder to bear as we weaken in body and spirit. Our yearning for the past is fueled by a selective memory of our younger selves.

28: Of all the forms of courage, the ability to laugh is the most profoundly therapeutic

To be able to experience fully the sadness and absurdity that life so often presents and still find reasons to go on is an act of courage abetted by our ability to both love and laugh. Above all, to tolerate the uncertainty we must feel in the face of the large questions of existence requires that we cultivate an ability to experience moments of pleasure. In this sense all humor is “gallows humor,” laughter in the face of death.

29: Mental health requires freedom of choice.

When we are depressed our loss of energy, inability to concentrate, and sad mood customarily cause us to withdraw from the people and activities that previously gave us pleasure. Our ability to work is compromised and in extreme cases we lose our will to live altogether. Similarly, excessive anxiety usually results in various avoidance behaviors that attempt to reduce the worry and nervousness with which we are beset. In the case of major mental illness, manic depression or schizophrenia, our loss of touch with reality prevents us from engaging the world freely.

30: Forgiveness is a form of letting go, but they are not the same thing.

Life can be seen as a series of relinquishments, rehearsals for the final act of letting go of our earthly selves. Why, then, is it so hard for people to surrender the past? Our memories, good and bad, are what give us a sense of continuity and link the many people we have been to the one that temporarily inhabits our changing body.

The collection of habits and conditioned responses that renders us unique serves as a kind of gyroscope, lending our responses to life predictability that is of value both to us and to those who seek to know us. Our former selves can also serve as a sort of anchor, providing stability while sometimes inhibiting adaptation to new circumstances.

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

5 Comments

Pingback: 100 Books Reading Challenge 2021 – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: Winter is Coming. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: You are not Helpless. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: The Gift of getting fired. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: On New Years Resolution. | Lanre Dahunsi