“Most history is guessing, and the rest is prejudice.”

Print | Kindle(eBook) | Audiobook

The Lesson of History is a great book that distills the themes and lessons observed from 5,000 years of world history. The book is by the Husband and Wife pair of William and Ariel Durant, historians and winners of the 1968 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction for their 11-volume book, The Story of Civilization.

The major lesson of history, according to the Durants: Human Nature has not really changed, but Human behavior has evolved. The Lessons learned from history were examined from 12 perspectives:

- geography, biology, race, character, morals, religion, economics, socialism, government, war, growth and decay, and progress.

Here are my favourite takeaways from reading, The Lessons of History by Will and Ariel Durant.

“The present is the past rolled up for action, and the past is the present unrolled for understanding”

- “Civilization is social order promoting cultural creation. Four elements constitute it: economic provision, political organization, moral tradition, and the pursuit of knowledge and the arts. It begins where chaos and insecurity end. For when fear is overcome, curiosity and constructiveness are free, and man passes by natural impulse towards the understanding and embellishment of life.” (Will Durant, Story of Civilization, pg 1, vol. 1)”

- The historian always oversimplifies, and hastily selects a manageable minority of facts and faces out of a crowd of souls and events whose multitudinous complexity he can never quite embrace or comprehend.

History and the Earth - “History is but the record of crimes and misfortunes. – Voltaire

- History is subject to geology. Every day the sea encroaches somewhere upon the land, or the land upon the sea; cities disappear under the water, and sunken cathedrals ring their melancholy bells. Mountains rise and fall in the rhythm of emergence and erosion; rivers swell and flood, or dry up, or change their course; valleys become deserts, and isthmuses become straits. To the geologic eye all the surface of the earth is a fluid form, and man moves upon it as insecurely as Peter walking on the waves to Christ.

- Geography is the matrix of history, its nourishing mother and disciplining home. Its rivers, lakes, oases, and oceans draw settlers to their shores, for water is the life of organisms and towns, and offers inexpensive roads for transport and trade.

Biology and History - History is a fragment of biology: the life of man is a portion of the vicissitudes of organisms on land and sea. Sometimes, wandering alone in the woods on a summer day, we hear or see the movement of a hundred species of flying, leaping, creeping, crawling, burrowing things.

- The first biological lesson of history is that life is competition. Competition is not only the life of trade, it is the trade of life—peaceful when food abounds, violent when the mouths outrun the food.

- Animals eat one another without qualm; civilized men consume one another by due process of law. Co-operation is real, and increases with social development, but mostly because it is a tool and form of competition; we co-operate in our group—our family, community, club, church, party, “race,” or nation—in order to strengthen our group in its competition with other groups.

- We are subject to the processes and trials of evolution, to the struggle for existence and the survival of the fittest to survive. If some of us seem to escape the strife or the trials it is because our group protects us; but that group itself must meet the tests of survival.

- The second biological lesson of history is that life is selection. In the competition for food or mates or power some organisms succeed and some fail. In the struggle for existence some individuals are better equipped than others to meet the tests of survival.

Race and History - The role of race in history is rather preliminary than creative. Varied stocks, entering some locality from diverse directions at divers times, mingle their blood, traditions, and ways with one another or with the existing population, like two diverse pools of genes coming together in sexual reproduction. Such an ethnic mixture may in the course of centuries produce a new type, even a new people; so Celts, Romans, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes, and Normans fused to produce Englishmen.

- It is not the race that makes the civilization, it is the civilization that makes the people: circumstances geographical, economic, and political create a culture, and the culture creates a human type.

- History is color-blind and can develop a civilization (in any favorable environment) under almost any skin.

Character and History - Society is founded not on the ideals but on the nature of man, and the constitution of man rewrites the constitutions of states.

- Intellect is therefore a vital force in history, but it can also be a dissolvent and destructive power. Out of every hundred new ideas ninety-nine or more will probably be inferior to the traditional responses which they propose to replace. No one man, however brilliant or well-informed, can come in one lifetime to such fullness of understanding as to safely judge and dismiss the customs or institutions of his society, for these are the wisdom of generations after centuries of experiment in the laboratory of history.

- History in the large is the conflict of minorities; the majority applauds the victor and supplies the human material of social experiment.

Morals and History - Morals are the rules by which a society exhorts (as laws are the rules by which it seeks to compel) its members and associations to behavior consistent with its order, security, and growth. So for sixteen centuries the Jewish enclaves in Christendom maintained their continuity and internal peace by a strict and detailed moral code, almost without help from the state and its laws.

- A little knowledge of history stresses the variability of moral codes, and concludes that they are negligible because they differ in time and place, and sometimes contradict each other. A larger knowledge stresses the universality of moral codes, and concludes to their necessity.

- Moral codes differ because they adjust themselves to historical and environmental conditions. If we divide economic history into three stages—hunting, agriculture, industry—we may expect that the moral code of one stage will be changed in the next.

Religion and History - Religion does not seem at first to have had any connection with morals. Apparently (for we are merely guessing, or echoing Petronius, who echoed Lucretius) “it was fear that first made the gods” —fear of hidden forces in the earth, rivers, oceans, trees, winds, and sky. Religion became the propitiatory worship of these forces through offerings, sacrifice, incantation, and prayer.”

- One lesson of history is that religion has many lives, and a habit of resurrection. How often in the past have God and religion died and been reborn! Ikhnaton used all the powers of a pharaoh to destroy the religion of Amon; within a year of Ikhnaton’s death the religion of Amon was restored.

- I do not know what the heart of a rascal may be; I know what is in the heart of an honest man; it is horrible.” – Joseph de Maistre.

- “As long as there is poverty there will be gods.”

Economics and History - History, according to Karl Marx, is economics in action—the contest, among individuals, groups, classes, and states, for food, fuel, materials, and economic power. Political forms, religious institutions, cultural creations, are all rooted in economic realities.

- The experience of the past leaves little doubt that every economic system must sooner or later rely upon some form of the profit motive to stir individuals and groups to productivity. Substitutes like slavery, police supervision, or ideological enthusiasm prove too unproductive, too expensive, or too transient. Normally and generally men are judged by their ability to produce—except in war, when they are ranked according to their ability to destroy.

- In progressive societies the concentration may reach a point where the strength of number in the many poor rivals the strength of ability in the few rich; then the unstable equilibrium generates a critical situation, which history has diversely met by legislation redistributing wealth or by revolution distributing poverty.

Socialism and History - The struggle of socialism against capitalism is part of the historic rhythm in the concentration and dispersion of wealth. The capitalist, of course, has fulfilled a creative function in history: he has gathered the savings of the people into productive capital by the promise of dividends or interest; he has financed the mechanization of industry and agriculture, and the rationalization of distribution; and the result has been such a flow of goods from producer to consumer as history has never seen before.

- Capitalism retains the stimulus of private property, free enterprise, and competition, and produces a rich supply of goods; high taxation, falling heavily upon the upper classes, enables the government to provide for a self-limited population unprecedented services in education, health, and recreation. The fear of capitalism has compelled socialism to widen freedom, and the fear of socialism has compelled capitalism to increase equality. East is West and West is East, and soon the twain will meet.

Government and History

- The prime task of government is to establish order; organized central force is the sole alternative to incalculable and disruptive force in private hands. Power naturally converges to a center, for it is ineffective when divided, diluted, and spread.

- Monarchy seems to be the most natural kind of government, since it applies to the group the authority of the father in a family or of the chieftain in a warrior band. If we were to judge forms of government from their prevalence and duration in history we should have to give the palm to monarchy; democracies, by contrast, have been hectic interludes.

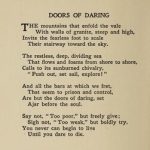

- The only real revolution is in the enlightenment of the mind and the improvement of character, the only real emancipation is individual, and the only real revolutionists are philosophers and saints.

- The excessive increase of anything causes a reaction in the opposite direction;… dictatorship naturally arises out of democracy, and the most aggravated form of tyranny and slavery out of the most extreme form of liberty.

Democracy is the most difficult of all forms of government, since it requires the widest spread of intelligence, and we forgot to make ourselves intelligent when we made ourselves sovereign. Education has spread, but intelligence is perpetually retarded by the fertility of the simple. A cynic remarked that “you mustn’t enthrone ignorance just because there is so much of it.” However, ignorance is not long enthroned, for it lends itself to manipulation by the forces that mold public opinion. It may be true, as Lincoln supposed, that “you can’t fool all the people all the time,” but you can fool enough of them to rule a large country.

History and War

War is one of the constants of history, and has not diminished with civilization or democracy. In the last 3,421 years of recorded history only 268 have seen no war. We have acknowledged war as at present the ultimate form of competition and natural selection in the human species.

The causes of war are the same as the causes of competition among individuals: acquisitiveness, pugnacity, and pride; the desire for food, land, materials, fuels, mastery. The state has our instincts without our restraints. The individual submits to restraints laid upon him by morals and laws, and agrees to replace combat with conference, because the state guarantees him basic protection in his life, property, and legal rights. The state itself acknowledges no substantial restraints, either because it is strong enough to defy any interference with its will or because there is no superstate to offer it basic protection, and no international law or moral code wielding effective force.

The Ten Commandments must be silent when self-preservation is at stake.

Growth and Decay

History repeats itself in the large because human nature changes with geological leisureliness, and man is equipped to respond in stereotyped ways to frequently occurring situations and stimuli like hunger, danger, and sex. But in a developed and complex civilization individuals are more differentiated and unique than in a primitive society, and many situations contain novel circumstances requiring modifications of instinctive response; custom recedes, reasoning spreads; the results are less predictable. There is no certainty that the future will repeat the past. Every year is an adventure.

Nations die. Old regions grow arid, or suffer other change. Resilient man picks up his tools and his arts, and moves on, taking his memories with him. If education has deepened and broadened those memories, civilization migrates with him, and builds somewhere another home. In the new land he need not begin entirely anew, nor make his way without friendly aid; communication and transport bind him, as in a nourishing placenta, with his mother country. Rome imported Greek civilization and transmitted it to Western Europe; America profited from European civilization and prepares to pass it on, with a technique of transmission never equaled before.

History is so indifferently rich that a case for almost any conclusion from it can be made by a selection of instance

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Print | Kindle(eBook) | Audiobook

1 Comment

Pingback: 100 Books Reading Challenge 2021 – Lanre Dahunsi