“You cannot force someone to want to change their behavior. After all, they are not just “behaviors” to the person suffering from the disorder—they are coping mechanisms they have used all their life.” — John M. Grohol, Psy.D.

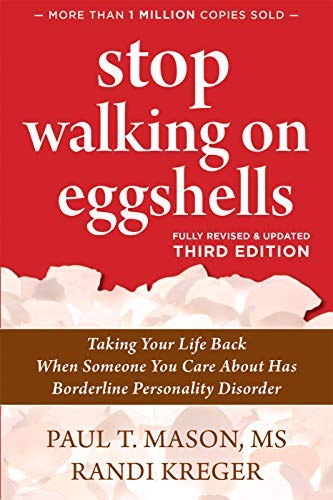

Title: Stop Walking on Eggshells: Taking Your Life Back When Someone You Care About Has Borderline Personality Disorder

Authors: Paul T. T. Mason MS and Randi Kreger

Year: 2020 – Third Edition

Living with someone with a personality disorder is a roller coaster of emotions and uncertainties. The disorder leads to emotional instability, negative self-image, and difficulty with interpersonal relationships. In Stop Walking on Eggshells, authors Randi Kreger and Paul T. T. Mason MS write about caring for someone with Borderline Personality Disorder, setting boundaries, and caring for yourself.

“Although you can’t change the person with BPD, you can change yourself. By examining your own behavior and modifying your actions, you can get off the emotional roller coaster and reclaim your life.”

Personality Disorder

Mayo Clinic defines personality disorders:

A personality disorder is a type of mental disorder in which you have a rigid and unhealthy pattern of thinking, functioning and behaving. A person with a personality disorder has trouble perceiving and relating to situations and people. This causes significant problems and limitations in relationships, social activities, work and school.

According to the DSM-IV-TR (2004), a personality disorder is:

an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectation of the individual’s culture, pervasive and inflexible (unlikely to change), stable over time, leads to distress or impairment in interpersonal relationships.

In the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), Borderline Personality Disorder diagnostic criteria reads as follows:

A pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects [moods], and marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a variety of contexts, as indicated by five (or more) of the following:

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Note: Do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behaviour covered in criterion 5.

- A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation.

- Identity disturbance: markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self.

- Impulsivity in at least 2 areas that are potentially self-damaging (e.g., spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating). Note: Do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behaviour covered in criterion 5.

- Recurrent suicidal behaviour, gestures or threats, or self-mutilating behaviour.

- Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood (e.g., intense episodic dysphoria, irritability or anxiety usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days).

- Chronic feelings of emptiness.

- Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger (e.g., frequent displays of temper, constant anger, recurrent physical fights).

- Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.

Splitting

People with BPD often perceive other people as either the wicked witch or fairy godmother, a saint or a demon. When you seem to be meeting their needs, they cast you in the role of superhero. But when they perceive that you’ve failed them, you become the villain.

“Because people with BPD have a hard time integrating a person’s good and bad traits, their current opinion of someone is often based on their last interaction with them—like someone who lacks a short-term memory.“

Dissociation

People with BPD may dissociate to different degrees to escape from painful feelings or situations. The more stressful the situation, the more likely it is that the person will dissociate. In extreme cases, people with BPD may even lose all contact with reality for a brief period of time. If the borderline in your life reports memories of shared situations quite differently from you, dissociation may be one possible explanation.

Control Issues

Borderlines may need to feel in control of other people because they feel so out of control with themselves. In addition, they may be trying to make their own world more predictable and manageable. People with BPD may unconsciously try to control others by putting them in no-win situations, creating chaos that no one else can figure out, or accusing others of trying to control them.

Feelings create facts

In general, emotionally healthy people base their feelings on facts. People with BPD, however, may do the opposite. When their feelings don’t fit the facts, they may unconsciously revise the facts to fit their feelings. This may be one reason why their perception of events is different from yours.

Projection

Projection is denying one’s own unpleasant traits, behaviors, or feelings by attributing them—often in an accusing way—to someone else.

Tools for taking back control of your life

Tool 1: Take good care of yourself: obtaining support and finding community, detaching with love, getting a handle on your emotions, improving self-esteem, mindfulness, laughter, and wellness.

Tool 2: Uncover what keeps you feeling stuck: owning your choices; helping others without rescuing; and handling fear, obligation, and guilt.

Tool 3: Communicate to be heard: putting safety first, handling rage, active listening, nonverbal communication, defusing anger and criticism, validation and empathetic acknowledging.

Tool 4: Set limits with love: boundary issues, “sponging” and “mirroring,” preparing for discussions, persisting for change, and the DEAR (Describe, Express, Assert, and Reinforce) technique.

Tool 5: Reinforce the right behaviors: the effects of intermittent reinforcement.

What You Can Do – Change yourself

There is nothing wrong with wanting to change the person with BPD in your life. You may be right: he might be a lot happier and your relationship might improve if he sought help for BPD. But in order for you to get off the emotional roller coaster, you will have to give up the fantasy that you can or should change someone else. When you let go of this belief, you will be able to claim the power that is truly yours: the power to change yourself.

Consider a lighthouse. It stands on the shore with its beckoning light, guiding ships safely into the harbor. The lighthouse can’t uproot itself, wade out into the water, grab the ship by the stern, and say, “Listen, you fool! If you stay on this path, you may break up on the rocks!

No, the ship has some responsibility for its own destiny. It can choose to be guided by the lighthouse. Or it can go its own way. The lighthouse is not responsible for the ship’s decisions. All it can do is be the best lighthouse it knows how to be.

Focus on your own issues

Some people find that trying to change someone else is easier than changing themselves and that focusing on the problems of others helps them avoid their own problems.

“Allow people to be who they are instead of what you want them to be. Send healthy support messages like, “I’m here if you need me, but your choices—and the consequences—belong to you.”

Take responsibility for your own behaviour

You may feel like a crumpled newspaper in a tornado, buffeted about at the whim of the person in your life with BPD. But you have more control over the relationship than you probably think you do. You have power over your own actions. And you control your own reactions to troublesome BPD behavior. Once you understand yourself and the decisions you’ve made in the past, it is easier to make new decisions that may be healthier for you and the relationship in the long run.

Memorize the three Cs and the three Gs:

- I didn’t cause it.

- I can’t control it.

- I can’t cure it.

- get off the BP’s back.

- get out of the BP’s way.

- get on with your own life.

Healthy limits are somewhat flexible, like a soft piece of plastic. You can bend them, and they don’t break. When your limits are overly flexible, however, violations and intrusions can occur. You may take on the feelings and responsibilities of others and lose sight of your own.

Determine your Personal limits

Boundaries without consequences is nagging.

Personal limits, or boundaries, tell you where you end and where others begin. Limits define who you are, what you believe, how you treat other people, and how you let them treat you. Like the shell of an egg, limits give you form and protect you. Like the rules of a game, they bring order to your life and help you make decisions that benefit you.

“Setting and enforcing boundaries is not selfish. It is normal and necessary. Some non-BPs label their behavior “selfish” when they are simply watching out for themselves.”

Stages of Grief

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, author of Death: The Final Stage of Growth (1975), outlined five stages of grief, which are appropriate for people who care about someone with BPD.

Denial

Non-BPs make excuses for the BPs’ behavior or refuse to believe that their behavior is unusual. The more isolated the non-BP, the greater the chances they will be in denial. This is because without outside input, non-BPs lose their sense of perspective about what is normal. People with BPD can be skillful at convincing others that their behavior is the non-BP’s fault. This keeps non-BPs in a continual state of denial.

Anger

Some non-BPs respond to angry attacks by fighting back. This is like adding gasoline to a fire. Other non-BPs maintain that anger is an inappropriate response to borderline behavior. Some say, “You wouldn’t get mad at someone for having diabetes—why would you be angry when they have BPD?”

Feelings don’t have IQs. They just are. Sadness, anger, guilt, confusion, hostility, annoyance, frustration—all are normal, and to be expected by people faced with borderline behavior. This is true no matter what your relationship is to the person with BPD. This doesn’t mean that you should respond to the BP with anger. But it does mean that you need a safe place to vent your emotions and feel accepted, not judged.

Bargaining

This stage is characterized by the non-BP making concessions in order to bring back the “normal” behavior of the person they love. The thinking goes, “If I do what this person wants, I will get what I need in this relationship.” We all make compromises in relationships. But the sacrifices that people make to satisfy the borderlines they care about can be very costly. And the concessions may never be enough. Before long, more proof of love is needed and another bargain must be struck.

Depression

Depression sets in when non-BPs realize the true cost of the bargains they’ve made: loss of friends, family, self-respect, and hobbies. The person with BPD hasn’t changed. But the non-BP has.

Acceptance

Acceptance comes when non-BPs integrate the “good” and “bad” aspects of the borderlines they care about and realize that the BPs are not one or the other, but both. Non-BPs in this stage have learned to accept responsibility for their own choices and hold other people accountable for their choices as well. Each can then make their own decisions about the relationship with a clearer understanding of themselves and the person with BPD.

Making decisions about your relationship

People who care about someone with BPD are usually in a great deal of pain. Staying in the relationship as it is seems unbearable. But leaving seems unthinkable or impossible.

Predictable stages

People who love someone with BPD seem to go through similar stages. The longer the relationship has lasted, the longer each stage seems to take. Although these are listed in the general order in which people go through them, most people move back and forth among different stages.

Confusion stage

This generally occurs before a diagnosis of BPD is known. Non-BPs struggle to understand why borderlines sometimes behave in ways that seem to make no sense. They look for solutions that seem elusive, blame themselves, or resign themselves to living in chaos.

Outer-directed Stage

In this stage, non-borderlines:

turn their attention toward the person with the disorder

urge the BP to seek professional help, attempting to get him or her to change

try their best not to trigger problematic behavior

learn all they can about BPD in an effort to understand and empathize with the person they care about

BPs often suppress their anger and instead experience depression, hopelessness, and guilt.

The chief tasks for non-BPs in this stage include:

acknowledging and dealing with their own emotions

letting BPs take responsibility for their own actions

giving up the fantasy that BPs will behave as the non-BPs would like them to

Inner-directed stage

Eventually, non-BPs look inward and conduct an honest appraisal of themselves. It takes two people to have a relationship, and the goal for non-BPs in this stage is to better understand their role in making the relationship what it now is. The objective here is not self-recrimination but insight and self-discovery.

Decision-making stage

Armed with knowledge and insight, non-BPs struggle to make decisions about the relationship. This stage can often take months or years. Non-BPs in this stage need to clearly understand their own values, beliefs, expectations, and assumptions.

Resolution phase

In this final stage, non-BPs implement their decisions and live with them. Depending upon the type of relationship, some non-BPs may, over time, change their minds many times and try different alternatives.

“As an adult, when the relationship causes too much pain and your relative is unwilling to change, you have the option to temporarily or permanently step away.”

All the Best in your quest to get Better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

2 Comments

Pingback: 100 Books Reading Challenge 2021 – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: 7 Strategies for dealing with the narcissist. | Lanre Dahunsi