“Only when we realize we can’t hold on to anything can we begin to relax our efforts to control our experience.”

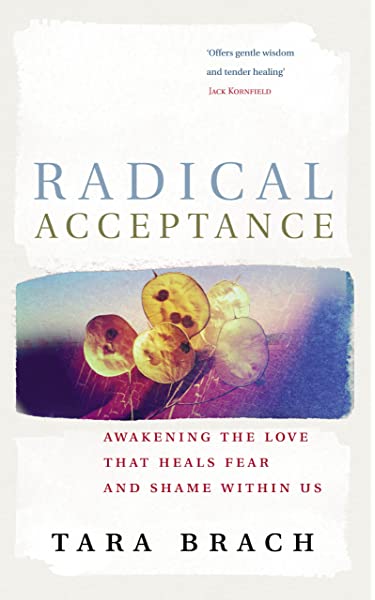

Print | Kindle(eBook) | Audiobook

In Radical Acceptance, Tara Brach explores in depth how Buddhist teachings can transform our fear and shame. Through meditation, mindfulness practices and fully understanding the healing power of compassion, we can discover the very real possibility of meeting imperfection in ourselves and others with courage and love – and so transform our lives.

Radical Acceptance does not mean defining ourselves by our limitations. It is not an excuse for withdrawal.

Part of the practice of Radical Acceptance is knowing that, whatever arises, whatever we can’t embrace with love, imprisons us — no matter what it is. If we are at war with it, we stay in prison. It is for the freedom and healing of our own hearts, that we learn to recognize and allow our inner life.

According to Brach, there are two wings of radical acceptance: seeing clearly (Mindfulness) and holding our experience with compassion (Self Compassion).

We suffer when we cling to or resist experience, when we want life different than it is. As the saying goes: “Pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional.

Here are my Favourite take-aways from reading, Radical Acceptance: Awakening the Love that Heals Fear and Shame by Tara Brach:

Seeing Clearly (Mindfulness) : Clear Recognition

“We can’t honestly accept an experience unless we see clearly what we are accepting.”

- The wing of clear seeing is often described in Buddhist practice as mindfulness. This is the quality of awareness that recognizes exactly what is happening in our moment-to-moment experience. When we are mindful of fear, for instance, we are aware that our thoughts are racing, that our body feels tight and shaky, that we feel compelled to flee—and we recognize all this without trying to manage our experience in any way, without pulling away. Our attentive presence is unconditional and open—we are willing to be with whatever arises, even if we wish the pain would end or that we could be doing something else.

“Only when we realize we can’t hold on to anything can we begin to relax our efforts to control our experience.”

Compassion: Compassionate Presence

- The second wing of Radical Acceptance, compassion, is our capacity to relate in a tender and sympathetic way to what we perceive. Instead of resisting our feelings of fear or grief, we embrace our pain with the kindness of a mother holding her child. Rather than judging or indulging our desire for attention or chocolate or sex, we regard our grasping with gentleness and care. Compassion honors our experience; it allows us to be intimate with the life of this moment as it is. Compassion makes our acceptance wholehearted and complete.

“The two wings of Radical Acceptance free us from this swirling vortex of reaction. They help us find the balance and clarity that can guide us in choosing what we say or do.”

- We lay the foundations of Radical Acceptance by recognizing when we are caught in the habit of judging, resisting and grasping, and how we constantly try to control our levels of pain and pleasure. We lay the foundations of Radical Acceptance by seeing how we create suffering when we turn harshly against ourselves, and by remembering our intention to love life.

- As we let go of our stories of what is wrong with us, we begin to touch what is actually happening with clear and kind attention. We release our plans or fantasies and arrive openhanded in the experience of this moment. Whether we feel pleasure or pain, the wings of acceptance allow us to honor and cherish this ever-changing life, as it is.

“Don’t turn away. Keep your gaze on the bandaged place. That’s where the light enters you.” – Rumi

- Radical Acceptance enables us to return to the root or origin of who we are, to the source of our being. When we are unconditionally kind and present, we directly dissolve the trance of unworthiness and separation. In accepting the waves of thought and feeling that arise and pass away, we realize our deepest nature, our original nature, as a boundless sea of wakefulness and – love.

Living in Trance

- “For so many of us, feelings of deficiency are right around the corner. It doesn’t take much—just hearing of someone else’s accomplishments, being criticized, getting into an argument, making a mistake at work—to make us feel that we are not okay.”

- “As a friend of mine put it, “Feeling that something is wrong with me is the invisible and toxic gas I am always breathing.” When we experience our lives through this lens of personal insufficiency, we are imprisoned in what I call the trance of unworthiness. Trapped in this trance, we are unable to perceive the truth of who we really are.”

- “Radical Acceptance reverses our habit of living at war with experiences that are unfamiliar, frightening or intense. It is the necessary antidote to years of neglecting ourselves, years of judging and treating ourselves harshly, years of rejecting this moment’s experience. Radical Acceptance is the willingness to experience ourselves and our life as it is. A moment of Radical Acceptance is a moment of genuine freedom.”

Radical Acceptance is the willingness to experience ourselves and our life as it is. A moment of Radical Acceptance is a moment of genuine freedom.

THE TRANCE OF UNWORTHINESS

- “Feeling unworthy goes hand in hand with feeling separate from others, separate from life. If we are defective, how can we possibly belong? It’s a vicious cycle: The more deficient we feel, the more separate and vulnerable we feel. Underneath our fear of being flawed is a more primal fear that something is wrong with life, that something bad is going to happen. Our reaction to this fear is to feel blame, even hatred, toward whatever we consider the source of the problem: ourselves, others, life itself. But even when we have directed our aversion outward, deep down we still feel vulnerable.”

“Convinced that we are not good enough, we can never relax. We stay on guard, monitoring ourselves for shortcomings. When we inevitably find them, we feel even more insecure and undeserving. We have to try even harder. The irony of all of this is . . . where do we think we are going anyway?”

Keeping Busy

- “Staying occupied is a socially sanctioned way of remaining distant from our pain. How often do we hear that someone who has just lost a dear one is “doing a good job at keeping busy”? If we stop we run the risk of plunging into the unbearable feeling that we are alone and utterly worthless. So we scramble to fill ourselves—our time, our body, our mind. We might buy something new or lose ourselves in mindless small talk. As soon as we have a gap, we go on-line to check our e-mail, we turn on music, we get a snack, watch television—anything to help us bury the feelings of vulnerability and deficiency lurking in our psyche.”

- When we strive to impress or outdo others, we strengthen the underlying belief that we are not good enough as we are. This doesn’t mean that we can’t compete in a healthy way, put wholehearted effort into work or acknowledge and take pleasure in our own competence. But when our efforts are driven by the fear that we are flawed, we deepen the trance of unworthiness.

The Sacred Pause

- In our lives, we often find ourselves in situations we can’t control, circumstances in which none of our strategies work. Helpless and distraught, we frantically try to manage what is happening.

- Our child takes a downward turn in academics, and we issue one threat after another to get him in line. Someone says something hurtful to us, and we strike back quickly or retreat. We make a mistake at work, and we scramble to cover it up or go out of our way to make up for it. We head into emotionally charged confrontations nervously rehearsing and strategizing. The more we fear failure the more frenetically our bodies and minds work. We fill our days with continual movement: mental planning and worrying, habitual talking, fixing, scratching, adjusting, phoning, snacking, discarding, buying, looking in the mirror.

- “Pausing is the gateway to Radical Acceptance. In the midst of a pause, we are giving room and attention to the life that is always streaming through us, the life that is habitually overlooked. It is in this rest under the bodhi tree that we realize the natural freedom of our heart and awareness. Like the Buddha, rather than running away, we need only commit ourselves to arriving, here and now, with wholehearted presence.”

“When we pause, we don’t know what will happen next. But by disrupting our habitual behaviors, we open to the possibility of new and creative ways of responding to our wants and fears.”

- “Most of us spend years trying to cloister ourselves inside the palace walls. We chase after the pleasure and security we hope will give us lasting happiness. Yet no matter how happy we may be, life inevitably delivers up a crisis—divorce, death of a loved one, a critical illness. Seeking to avoid the pain and control our experience, we pull away from the intensity of our feelings, often ignoring or denying our genuine physical and emotional needs.”

- Whenever you find you are stuck or disconnected, you can begin your life fresh in that moment by pausing, relaxing and paying attention to your immediate experience.

“When we learn to face and feel the fear and shame we habitually avoid, we begin to awaken from trance. We free ourselves to respond to our circumstances in ways that bring genuine peace and happiness.“

- “We practice Radical Acceptance by pausing and then meeting whatever is happening inside us with this kind of unconditional friendliness. Instead of turning our jealous thoughts or angry feelings into the enemy, we pay attention in a way that enables us to recognize and touch any experience with care.“Nothing is wrong—whatever is happening is just “real life.” Such unconditional friendliness is the spirit of Radical Acceptance.”

Naming and Noting

- “Like inquiry, noting is an opportunity to communicate unconditional friendliness to our inner life. If fear arises and we pounce on it with a name, “Fear! Gotcha!” we’re only creating more tension. Naming an experience is not an attempt to nail an unpleasant experience or make it go away. Rather, it is a soft and gentle way of saying, “I see you, Mara.” This attitude of Radical Acceptance makes it safe for the frightened and vulnerable parts of our being to let themselves be known.”

“Recognizing that we are suffering is freeing—self-judgment falls away and we can regard ourselves with kindness.”

- “When we offer to ourselves the same quality of unconditional friendliness that we would offer to a friend, we stop denying our suffering. As we figuratively sit beside ourselves and inquire, listen and name our experience, we see Mara clearly and open our heart in tenderness for the suffering before us.”

Pain

Like every aspect of our evolutionary design, the unpleasant sensations we call pain are an intelligent part of our survival equipment: Pain is our body’s call to pay attention, to take care of ourselves.

- While fear of pain is a natural human reaction, it is particularly dominant in our culture, where we consider pain as bad or wrong. Mistrusting our bodies, we try to control them in the same way that we try to manage the natural world. We use painkillers, assuming that whatever removes pain is the right thing to do. This includes all pain—the pains of childbirth and menstruating, the common cold and disease, aging, and death. In our society’s cultural trance, rather than a natural phenomenon, pain is regarded as the enemy. Pain is the messenger we try to kill, not something we allow and embrace.

- When pain is traumatic, the trance can become full-blown and sustained. The victim pulls away from pain in the body with such fearful intensity that the conscious connection between body and mind is severed. This is called dissociation. All of us to some degree disconnect from our bodies, but when we live bound in fear of perceived ever-present danger, finding our way back can be a long and delicate process.

Facing Fear

- Facing fear is a lifelong training in letting go of all we cling to—it is a training in how to die. We practice as we face our many daily fears—anxiety about performing well, insecurity around certain people, worries about our children, about our finances, about letting down people we love. Our capacity to meet the ongoing losses in life with Radical Acceptance grows with practice. In time we find that we can indeed handle fear, including that deepest fear of losing life itself.

- Our willingness to face our fear frees us from trance and bestows on us the blessings of awareness. We let go of deeper and subtler layers of resistance until there is nothing left to resist at all, there is only awake and open awareness. This is the refuge that has room for both living and dying. In this radiant and changeless awareness we can, as Rilke puts it, “contain death, the whole of death . . . can hold it in one’s heart gentle, and not . . . refuse to go on living. Radical Acceptance of fear carries us to this source of all freedom, to the ultimate refuge that is our true home.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

8 Comments

Pingback: Top Books for Dealing with Grief and Loss. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: 100 Books Reading Challenge 2020 – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: You are already naked. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: You are not Helpless. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: The Gift of getting fired. – Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: 7 Strategies for dealing with the narcissist. | Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: | Lanre Dahunsi

Pingback: Tara Brach on Radical Acceptance and Radical Compassion. | Lanre Dahunsi