Addiction is an outcome—not the only one possible, but a prevalent one—of childhood trauma.

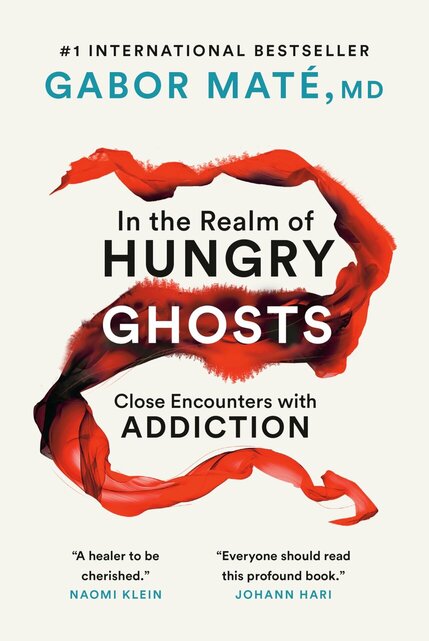

In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction, Canadian physician, addiction expert and author Dr. Gabor Maté argues that all addiction is a case of human development gone askew. The book is based on Dr. Matés’ experience as a medical doctor in Vancouver’s drug ghetto and on extensive interviews with his patients”.

“The question is never “Why the addiction?” but “Why the pain?”

Addiction arises from out thwarted ability to ourselves, love others in the ways that we all need. Opening our heart is the path to healing addiction

The Domain of Addiction

The inhabitants of the hungry ghost realm are depicted as creatures with scrawny necks, small mouths, emaciated limbs, and large, bloated, empty bellies. This is the domain of addiction, where we constantly seek something outside ourselves to curb an insatiable yearning for relief or fulfillment. The aching emptiness is perpetual because the substances, objects, or pursuits we hope will soothe it are not what we really need. We don’t know what we need, and so long as we stay in the hungry ghost mode, we’ll never know. We haunt our lives without being fully present.

“No society can understand itself without looking at its shadow side.”

Pain as the Root of Addiction

Addictions always originate in pain, whether felt openly or hidden in the unconscious. They are emotional anesthetics. Heroin and cocaine, both powerful physical painkillers, also ease psychological discomfort. Infant animals separated from their mothers can be soothed readily by low doses of narcotics, just as if it were actual physical pain they were enduring.

A hurt is at the center of all addictive behaviors. It is present in the gambler, the Internet addict, the compulsive shopper, and the workaholic. The wound may not be as deep and the ache not as excruciating, and it may even be entirely hidden—but it’s there.

Addiction: More about desire than attainment

Addictions, even as they resemble normal human yearnings, are more about desire than attainment. In the addicted mode, the emotional charge is in the pursuit and the acquisition of the desired object, not in the possession and enjoyment of it. The greatest pleasure is in the momentary satisfaction of yearning.

An addictus was a person who, having defaulted on a debt, was assigned to his creditor as a slave—hence addiction’s modern sense as enslavement to a habit.

Who’s in charge?

Any passion can become an addiction; but then how to distinguish between the two? The central question is: who’s in charge, the individual or their behavior? It’s possible to rule a passion, but an obsessive passion that a person is unable to rule is an addiction. And the addiction is the repeated behavior in which a person keeps engaging, even though he knows it harms himself or others.

Passion vs Addiction

The difference between passion and addiction is that between a divine spark and a flame that incinerates.

Passion is divine fire: it enlivens and makes holy; it gives light and yields inspiration. Passion is generous because it’s not ego-driven; addiction is self-centered. Passion gives and enriches; addiction is a thief. Passion is a source of truth and enlightenment; addictive behaviors lead you into darkness.

Addiction is passion’s dark simulacrum and, to the naive observer, its perfect mimic. It resembles passion in its urgency and in the promise of fulfillment, but its gifts are illusory. It’s a black hole. The more you offer it, the more it demands. Unlike passion, its alchemy does not create new elements from old. It only degrades what it touches and turns it into something less, something cheaper.

Addiction is centrifugal. It sucks energy from you, creating a vacuum of inertia. A passion energizes you and enriches your relationships. It empowers you and gives strength to others. Passion creates; addiction consumes—first the self and then the others within its orbit.

Addiction is any repeated behavior, substance-related or not, in which a person feels compelled to persist, regardless of its negative impact on his life and the lives of others. Addiction involves:

- compulsive engagement with the behavior, a preoccupation with it;

- impaired control over the behavior;

- persistence or relapse despite evidence of harm; and

- dissatisfaction, irritability, or intense craving when the object—be it a drug, activity, or other goal—is not immediately available.

Addiction is a deeply ingrained response to stress, an attempt to cope with it through self-soothing. Maladaptive in the long term, it is highly effective in the short term.

Any repeated behavior, substance-related or not, in which a person feels compelled to persist, regardless of its negative impact on his life and the lives of others. The distinguishing features of any addiction are compulsion, preoccupation, impaired control, persistence, relapse, and craving.

Nothing like a good addiction

There is no such thing as a good addiction. Everything a person can do is better done if there is no addictive attachment that pollutes it. For every addiction—no matter how benign or even laudable it seems from the outside—someone pays a price.

No human being is empty or deficient at the core, but many live as if they were and experience themselves primarily that way. Attempting to obliterate the sense of deficiency and emptiness that is a core state of any addict is like laboring to fill in a canyon with shovelfuls of dust. Energy devoted to such an end less and futile task is robbed from one’s psychological and spiritual growth, from genuinely soul-satisfying pursuits, and from the ones we love.

“As a rule, whatever we don’t deal with in our lives, we pass on to our children. Our unfinished emotional business becomes theirs. As a therapist said to me, “Children swim in their parents’ unconscious like fish swim in the sea.”

Emptiness based in abject fear.

At the core of every addiction is an emptiness based in abject fear. The addict dreads and abhors the present moment; she bends feverishly only toward the next time, the moment when her brain, infused with her drug of choice, will briefly experience itself as liberated from the burden of the past and the fear of the future—the two elements that make the present intolerable.

Many of us resemble the drug addict in our ineffectual efforts to fill in the spiritual black hole, the void at the center, where we have lost touch with our souls, our spirit—with those sources of meaning and value that are not contingent or fleeting. Our consumerist, acquisition-, action-, and image-mad culture only serves to deepen the hole, leaving us emptier than before.

If we are to help addicts,we must strive to change not them but their environments

To expect an addict to give up her drug is like asking the average person to imagine living without all his social skills, support networks, emotional stability, and sense of physical and psychological comfort. Those are the qualities that drugs, in their illusory and evanescent way, give the addict.

The problem’s not that the truth is harsh but that liberation from ignorance is as painful as being born. Run after truth until you’re breathless. Accept the pain involved in re-creating yourself afresh. These ideas will take a life to comprehend, a hard one interspersed with drunken moments. – NAGUIB MAHFOUZ, Palace of Desire

Fear and Resentment

The dominant emotions suffusing all addictive behavior are fear and resentment—an inseparable vaudeville team of unhappiness.

One prompts and sets up the other: fear of the way things are and resentment that they are that way; fear of life and resentment that life is as difficult as it is; fear of unpleasant mind-states and resentment that unpleasant moods and thoughts persist; fear that we’ll never feel all right and resentment that we cannot feel the way we want to; fear of the present and the future and resentment that we cannot control destiny.

The Four-Step Self-Treatment Method.

The program devised at the UCLA School of Medicine by Dr. Jeffrey Schwartz for the treatment of OCD is formally called the Four-Step Self-Treatment Method.

Step One: Relabel

In step one you label the addictive thought or urge exactly for what it is, not mistaking it for reality. When we relabel, we give up the language of need.

Example

“I say to myself, “I don’t need to purchase anything now or to eat anything now; I’m only having an obsessive thought that I have such a need. It’s not a real, objective need but a false belief. I may have a feeling of urgency, but there is actually nothing urgent going on.”

The point of relabeling is not to make the addictive urge disappear—it’s not going to, at least not for a long time, since it was wired into the brain long ago. It is strengthened every time you give in to it and every time you try to suppress it forcibly. The point is to observe it with conscious attention without assigning the habitual meaning to it. It is no longer a “need,” only a dysfunctional thought.

Step Two: Reattribute

In Re-attribute you learn to place the blame squarely on your brain. This is my brain sending me a false message. This step is designed to assign the relabeled addictive urge to its proper source.

If you change how you respond to those old circuits, you will eventually weaken them. They will persist for a long time—perhaps even all your life, but only as shadows of themselves. They will no longer have the weight, the gravitational pull, or the appeal they once boasted. You will no longer be their marionette.

Step Three: Refocus

In the refocus step you buy yourself time. Although the compulsion to open the bag of cookies or turn on the TV or drive to the store or the casino is powerful, its shelf life is not permanent. Being a mind-phantom, it will pass, and you have to give it time to pass.

The purpose of refocusing is to teach your brain that it doesn’t have to obey the addictive call. It can exercise the “free won’t.” It can choose something else. Perhaps in the beginning you can’t even hold out for fifteen minutes—fine. Make it five, and record it in a journal as a success. Next time, try for six minutes, or sixteen. This is not a hundredmeter dash but a solo marathon you are training for. Successes will come in increments.

Step Four: Revalue

Its purpose is to help you drive into your own thick skull just what has been the real impact of the addictive urge in your life: disaster. In this revalue step you will remind yourself why you’ve gone to all this trouble. The more clearly you see how things are, the more liberated you will be.

Step Five: Re-Create

Life, until now, has created you. You’ve been acting according to ingrained mechanisms wired into your brain before you had a choice in the matter, and it’s out of those automatic mechanisms that you’ve created the life you now have. It is time to re-create: to choose a different life.

Anger—the addicted mind’s way of resisting shame

Addiction floods in where self-knowledge—and therefore divine knowledge—are missing. To fill the unendurable void, we become attached to things of the world that cannot possibly compensate us for the loss of who we are.

The psyche of the addict is populated by demons more frightful than those many other people have to face, but if she undertakes the quest, she’ll find they are no more real and no more powerful. The reward at journey’s end, the treasure the hero has been seeking, is our essential nature.

Healing occurs in a sacred place located within us all: “When you know yourselves, then you will be known.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.