“When others hold our pens, we live with a constant gnawing fear of their disapproval. Their feedback is no longer an indictment of our behavior; it is an audit of our worth.

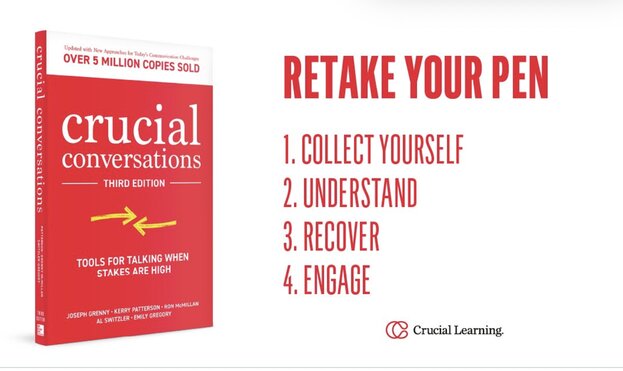

In their insightful book, Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High, authors Joseph Grenny, Kerry Patterson et al write about “The Other Side Academy (TOSA) Game” and the concept of retaking one’s pen.

The Other Side Academy

The Other Side Academy is a training school in which students learn pro-social, vocational and life skills allowing them to emerge with a healthy life on “the other side”. Many of those who seek entrance into the Academy are convicts, substance abusers or homeless. TOSA teaches students both fundamental personal management and relationship skills such as keeping one’s promise, accountability, love, charity, and dependability.

RETAKE YOUR PEN Summary

When you find yourself reacting to hard feedback, remind yourself that your reaction is largely within your control. “Retake your pen” by taking steps to secure your safety and affirm your worth. Then use four skills to manage how you address the information others share:

- Collect yourself. Breathe deeply, name your emotions, and present yourself with soothing truths that establish your safety and worth.

- Understand. Be curious. Ask questions and ask for examples. And then just listen. Detach yourself from what is being “said as though it is being said about a third person.

- Recover. Take a time-out if needed to recover emotionally and process what you’ve heard.

- Engage. Examine what you were told. Look for truth rather than defensively poking holes in the feedback. If appropriate, reengage with the person who shared the feedback and acknowledge what you heard, what you accept, and what you commit to do. If needed, share your view of things in a noncombative way.

The Crucial Conversation authors write:

Every Tuesday and Friday night from 7 to 9 p.m., students gather for what TOSA calls “Games.” TOSA leaders use the term to remind students that, while like a sports game, TOSA Games can be intense and challenging, there are rules to keep them safe, they don’t last forever, and you can move on when they’re over. In Games, people sit in groups of 20 and give each other unvarnished feedback.

Games can be loud. Vocabulary is sometimes raw. A single student can be the focus of a score of colleagues for 15 to 20 minutes without letup.

Peers present you with evidence that you have acted dishonestly, manipulatively, lazily, selfishly, or arrogantly. There is little emphasis placed on diplomatic delivery of the message. Instead, peers focus on helping individuals learn to “take their game.” Taking your game means, in essence, learning to listen nondefensively. Older students advise you to “just listen. Then put it all in a bag and take it to your pillow tonight. There you can decide what is gold and what is crap.

Unsurprisingly, newer students don’t take their games very well. They withdraw, deny, or lash out against those who are telling them things they don’t want to hear. But that changes quickly. They soon learn to let others say whatever they want to say, however they want to say it. They discover that they are the only sure source of their own sense of safety and worth. That discovery is liberating. They stop blaming the world for how they feel and become responsible for their own serenity.

“The fundamental belief is that relentless exposure to truth is the best path to empathy, growth, and happiness.”

Metaphorically speaking, they learn to retake their pen.

Think of your pen as the power to define your worth. When you hold your pen, you get to author the terms. Is your worth intrinsic to you? Is it about how you look? Is it contingent on how much you achieve, how many people admire you, or whether a certain person returns your love?

You’re born with your pen firmly in your own grasp. Babies don’t fret over others’ opinions. We have no need for reassurance of something that seems beyond question. It doesn’t matter to us that Grandma wishes we looked more like her, that Uncle would have liked us better if we had brown eyes, or that our older sister wanted us to be a girl. But that changes as we grow. As we become more aware of the emotions and judgments of those around us, a line gets crossed. We no longer look to others simply for help, information, or companionship—things they are qualified to offer us. Without realizing it, we hand them our pen.

Whoever holds your pen can compose the terms of your well-being. Some days you’re in full possession of your pen. Some people like you. Some people don’t. Some things go well. Some go poorly. But your personal security doesn’t come from others’ opinions of you; it comes from an innate sense of your enduring worth. Your psychological stock doesn’t rise and fall based on whether someone laughs at your joke. You’ve got your pen.

But then one day a subtle shift happens without your awareness. You give a presentation that totally rocks. People nod when they should nod. They scribble notes at your every key insight. And at the end, a peer you’ve never spoken to tells you it was the best project pitch he’s ever seen. It feels good. Really good. The committee meets and approves your proposal. That feels even better. Then your boss pulls you aside and says: “I’ve got big plans for you. Let’s talk tomorrow.” You look down and see your pen is now missing. You know it’s circulating out there somewhere. But who cares? Life feels good.

A shift happens when we no longer look to others just for information. We begin to look to them for definition. We don’t simply enjoy others’ approval; we need it. From that moment we are fundamentally insecure. Those in possession of our pen now control our emotional well-being. As good as today feels, tomorrow is now pregnant with peril.

“If you live off a man’s compliments, you’ll die from his criticism.” ― Cornelius Lindsey

Sometimes we surrender our pens thoughtlessly. We don’t notice the moment our center of gravity shifts. We lean too far forward and move from enjoying praise to needing it. Sometimes we do it out of a naïve hope that outside evidence will take better care of us than we can of ourselves. And other times it’s just about a quick fix.

We are unwilling to do the work required to steady ourselves, preferring to lean on approval instead. Then a Crucial Conversation or two remind us that this way of living makes us fundamentally unstable.

“How you experience feedback has more to do with the location of your pen than the content of the message.”

Unworthiness

When others hold our pens, we live with a constant gnawing fear of their disapproval. Their feedback is no longer an indictment of our behavior; it is an audit of our worth. When we surrender our pen, we simultaneously abdicate responsibility for defining the terms of our own worthiness. We stop generating feelings of worth and start looking for them. And that search perpetuates our feelings of insecurity.

The Feedback CURE

Four tools help TOSA students from feeling defined by feedback to being beneficiaries of it. These tools redirect them inside rather than outside to secure their safety and worth.

The tools form the acronym CURE.

Collect yourself

Breathing deeply and slowly reminds you that you are safe. It signals that you don’t need to be preparing for physical defense. Being mindful of your feelings helps, too. Do your best to name them as you feel them. Naming them helps you put a little bit of daylight between you and the emotions. Are you hurt, scared, embarrassed, ashamed? If you can think about what you’re feeling, you gain more power over the feeling. Also, identifying, examining, and critiquing the stories that led to your feelings can help.

Naming them helps you put a little bit of daylight between you and the emotions.

Understand

Be curious. Ask questions and ask for examples. And then just listen. Focusing on understanding helps interrupt our tendency toward personalizing. It’s hard to beat yourself up when you’re busy solving a puzzle. The best “curiosity puzzle” is answering the question

“Why would a reasonable, rational, decent person say what he or she is saying?”

Detach yourself from what is being said as though it is being said about a third person. That will help you bypass the need to evaluate what you’re hearing. Simply act like a good reporter trying to understand the story.

Recover

It’s sometimes best at this point to ask for a time-out. Feelings of control bring feelings of safety. And you regain a sense of control when you exercise your right to respond when you’re truly ready. Explain that you want some time to reflect and you’ll respond when you have a chance to do so.

Give yourself permission to feel and recover from the experience before doing any evaluation of what you heard.

- TOSA, students sometimes simply say, “I will take a look at that.” They don’t agree. They don’t disagree. They simply promise to look sincerely at what they were told on their own timeline”

- You can end a challenging episode by simply saying: “It’s important to me that I get this right. I need some time. And I’ll get back to you to let you know where I come out.” Then use whatever practices work for you to reconnect with a sense of safety and worth.

Explain that you want some time to reflect and you’ll respond when you have a chance to do so.

Engage.

Examine what you were told. If you’ve done a good job reestablishing feelings of safety and worth, you’ll look for truth rather than defensively poking holes in the feedback. Sift through the bag/pool of meaning. Even if it’s 95 percent junk and 5 percent gold, look for the gold.

There is almost always at least a kernel of truth in what people are telling you. Scour the message until you find it. Then, if appropriate, reengage with the person who shared the feedback and acknowledge what you heard, what you accept, and what you commit to do. At times, this may mean sharing your view of things. If you’re doing so with no covert need for approval, you won’t need to be defensive or combative.

When we surrender our pen, we simultaneously abdicate responsibility for defining the terms of our own worthiness. We stop generating feelings of worth and start looking for them.

All the best in your quest to get better. Don’t Settle: Live with Passion.

Comments are closed.